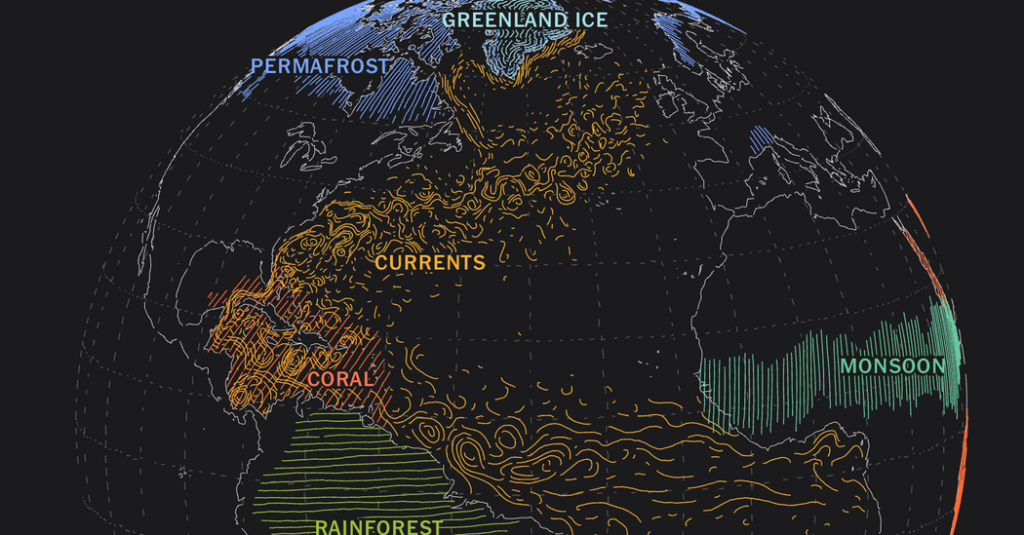

Now, we humans are reshaping the Earth's climate, little by little, every moment of every day. Hotter summers and wetter storms. Higher oceans and more intense wildfires. The dial of many threats to our homes, society, and surrounding environment is steadily turning upward.

We may also be changing the climate even more.

For the past two decades, scientists have been sounding the alarm that warming temperatures caused by carbon emissions are pushing nature's great systems toward collapse. These systems are so vast that they are able to maintain some level of balance as temperatures rise. But only up to a point.

Scientists say this balance could be disrupted if global warming exceeds a certain level. The effects will be far-reaching and difficult to reverse. It's like flipping a switch instead of turning a dial. Something that cannot be easily reversed.

mass death of coral reefs

Just because corals turn ghostly white doesn't necessarily mean they're dead, and it doesn't mean the reef is gone forever. When the water gets too hot, corals expel symbiotic algae within their tissues. If conditions improve, this bleaching can be tolerated. Over time, coral reefs can grow back. But as the world warms, occasional bleaching is becoming regular bleaching. Mild whitening becomes severe whitening.

Scientists' latest predictions are grim. Even if humans move quickly to curb global warming, 70 percent to 90 percent of today's reef-building corals could die in the next few decades. Otherwise, the damage could be more than 99 percent. Coral reefs appear healthy until the coral begins to bleach and die. Finally, it's the cemetery.

This does not necessarily mean that reef-building corals will become extinct. A sturdier one might survive being carried in a pocket. But the vibrant ecosystems these creatures support will become unrecognizable. No matter where corals currently live or how big they are, they won't recover quickly.

When it happens: It may already be underway.

Sudden thaw of permafrost

The remains of long-dead plants and animals have accumulated underground in colder parts of the world, and they contain large amounts of carbon, roughly twice the amount currently present in the atmosphere. When heat, wildfires, and rain thaw and destabilize the frozen ground, microbes come to work and convert this carbon into carbon dioxide and methane. These greenhouse gases exacerbate heat, fires, and rain, and accelerate snowmelt.

Like many of these large-scale, self-propelled changes in our climate, permafrost thaw is complex to predict. The freeze has already been lifted in large areas, including western Canada, Alaska and Siberia. But how quickly will the rest thaw, how much will it contribute to global warming, and how much carbon will remain trapped there as new plants sprout on top of it as it thaws? , all these are difficult to identify.

“These things are so uncertain that there's a bias not to talk about them or to ignore the possibility,” said Tapio Schneider, a climate scientist at the California Institute of Technology. “I think that's a mistake,” he said. “It is still important to investigate the risks, even if the likelihood of them occurring in the near future is relatively low.”

When it happens: Timing varies by location. Global warming impacts can accumulate over a century or more.

Greenland ice collapse

The huge ice sheets that cover the Earth's poles are not melting like ice cubes. Because of the size and geometric complexity of ice, many factors determine how quickly it loses its volume and contributes to sea level rise. Of these factors, scientists are particularly concerned about those that could start to undermine themselves and accelerate melting in ways that are very difficult to stop.

Altitude is an issue in Greenland. As the ice surface height decreases, more ice is located at warmer altitudes and exposed to warmer air. This will make it melt even faster.

Scientists know from geological evidence that much of Greenland was once ice-free. They also know that the effects of further large-scale melting could ripple around the world, affecting ocean currents and rainfall in the tropics and beyond.

When it will happen: Irreversible melting could begin this century and progress over hundreds or even thousands of years.

West Antarctic ice collapse

On the other side of the globe from Greenland, the ice in West Antarctica is threatened by warm water more than warm air.

Many of West Antarctica's glaciers drain into the sea, and their undersides are constantly inundated by ocean currents. As the water warms, these floating ice shelves become weaker from below as they melt, especially where they lie on the ocean floor. Like a dancer in a difficult pose, the shelf begins to lose its footing. With less floating ice holding the continents back, more ice from inside the continents will slide into the ocean. Eventually, the ice on the water's edge can no longer support its own weight and may break apart.

The West Antarctic ice sheet likely collapsed in Earth's distant past. Scientists are still trying to figure out how likely it is that today's ice will suffer the same fate.

“When you think about the future of the world's coastlines, 50 percent of the story will be the melting of Antarctica,” said David Holland, a New York University scientist who studies polar regions. Still, “we're still at day zero” when it comes to understanding how continental ice breaks up, he said.

When it will happen: As with Greenland, the ice sheet could begin to irreversibly retreat this century.

Sudden changes in the West African monsoon

About 15,000 years ago, the Sahara Desert began to turn green. It started when a small change in the Earth's orbit caused North Africa to become sunny every summer. This warmed the land and changed the direction of the winds, drawing in more humid air from over the Atlantic Ocean. As monsoon rains brought moisture down, grass grew and a lake the size of the Caspian Sea filled. Animals such as elephants, giraffes, and ancestral cattle flourished. So did humans, as the carvings and rock paintings of the time attest. It was only about 5,000 years ago that the region reverted to the harsh desert we know today.

Scientists now understand that the Sahara Desert has flipped several times over the years, between dry and wet, arid and temperate. There is less certainty about how, or whether, the West African monsoon will change or intensify in response to today's warming. (Despite its name, the region's monsoon also brings rain to parts of East Africa.)

Whatever happens will be critical for a region of the world where many people depend on the skies for their nutrition and livelihoods.

When it will happen: Hard to predict.

Loss of the Amazon rainforest

In addition to the presence of hundreds of indigenous communities, millions of plant and animal species, and 400 billion trees. Additionally, it includes countless other organisms that have not yet been discovered or named. In addition to being a rich store of carbon that can contribute to global warming, the Amazon rainforest plays another big role. It is a living, stirring, breathing weather engine.

The breath exhaled by all these trees together creates a thick cloud containing moisture. This reduction in moisture preserves the area's lush forests.

But now ranchers and farmers are cutting down trees, and global warming is worsening wildfires and droughts. Scientists fear that if more forest is lost, this rainfall system could fail and the remaining forests could dry up and turn into grassy savannahs.

Researchers recently estimated that half of the current Amazon forest could be at risk of undergoing this type of degradation by 2050.

When that happens depends on how quickly people cut down or protect remaining forests.

Interception of Atlantic currents

A huge loop of ocean water that flows from the west coast of Africa across the Atlantic Ocean, through the Caribbean Sea to Europe, and back down again determines temperature and precipitation over much of the planet. Saltier, denser water sinks to the depths, while fresher, lighter water rises and keeps this conveyor belt spinning.

But now, as Greenland's ice melts and vast new streams of freshwater flow into the North Atlantic, this balance is upset. Scientists fear that if the motor slows down too much, it could stall, potentially changing weather patterns for billions of people in Europe and the tropics.

Scientists have already seen signs of slowing in these ocean currents, which go by the confusing name of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The difficult part is predicting when a slowdown turns into a shutdown. Niklas Boers, a climate scientist at the Technical University of Munich and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, says data and records are currently too limited.

But we already know enough to be certain of one thing, Dr. Boas said. “For every gram of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the likelihood of a fall accident increases,” he says. “The longer we wait,” he said, to reduce emissions, “the further we move into dangerous territory.”

When it will happen: Very difficult to predict.

methodology

The range of warming levels that each tipping point could potentially trigger is determined by David I. Armstrong McKay et al., Science.

The shaded areas on the map indicate the current extent of the area associated with each natural system. These do not necessarily indicate precisely where large-scale changes are likely to occur if a tipping point is reached.