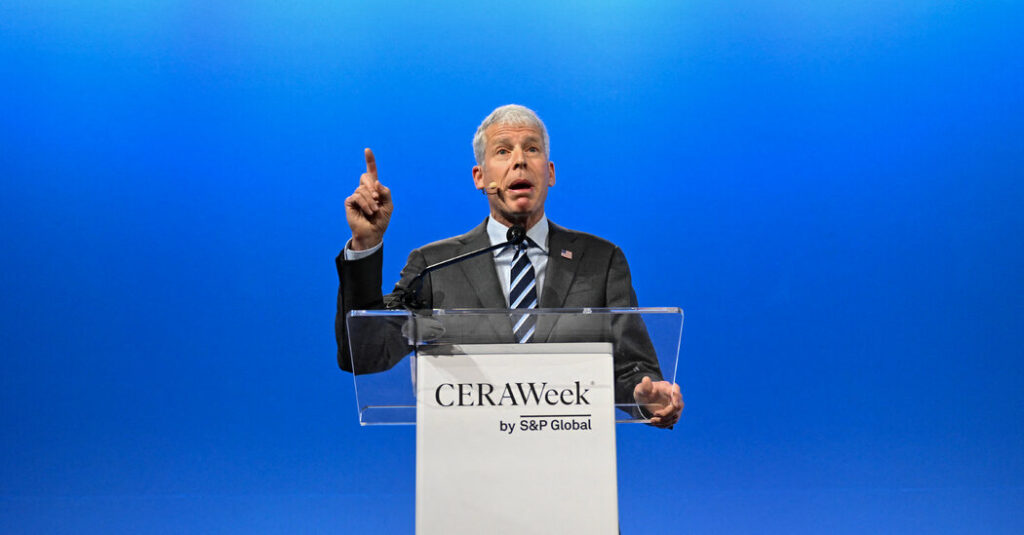

On Monday, massive oil and gas executives came to the crowd, and new US energy secretary Chris Wright made harsh criticism of the Biden administration's energy policy and efforts to combat climate change, pledging a “180 degree pivot.”

Wright, a former fracking executive, has emerged as the most powerful promoter of President Trump's plan to expand US oil and gas production and dismantle virtually all federal policies aimed at curbing global warming.

“We wanted to play a role in turning what we think is a very bad direction in energy policy,” Wright said he launched Cerawek at the S&P Global Conference in Houston, the country's largest annual meeting in the energy industry. “Previous administration policies have focused on climate change in a short-sighted way, and people are simply secondary damage.”

Wright's speech was greeted with enthusiastic applause.

It was quite different from a year ago when Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary for the Biden administration, told the same rally that the transition to low-carbon forms of energy, such as wind, solar and batteries, is unstoppable. “Even we are the world's largest producers of oil and gas, Granholm said:

But Wright had denied renewable electricity, but said he has played a small role in the global energy mix. Natural gas is currently supplying globally worldwide, before 25% of raw energy is converted into electricity or other uses. He said it only supplies around 3% of wind and solar. He said that gas also had a variety of other uses – it can be burned in furnaces to heat a home, or used to make fertilizers and other chemicals.

“Beyond obvious scale and cost issues, wind, solar and batteries cannot replace countless natural gas use,” Wright said.

Wright argues there is a moral case of fossil fuels, saying it is important to alleviate global poverty and is too fast to reduce the risk of emissions that raise energy prices around the world. He denounces the efforts of countries to stop adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere by 2050, calling it an “osinister goal.”

At a Washington meeting last week, Wright said African countries need more energy to lift themselves up from poverty, including coal, the most polluted fossil fuel. “We've been shamelessly telling Western countries that we don't develop coal, and we say coal is bad,” he said. “It's just nonsense.”

In Houston on Monday, other oil and gas executives reflected Wright's remarks, pitching oil and gas as the best solution for the poor in developing countries around the world.

Chevron CEO Michael Worth said: “That should not be acceptable, but affordable prices have at least left the conversation in the West.”

In recent years, much of the world has invested heavily in renewable energy. Last year, the country invested around $1.2 trillion in wind, solar, batteries and electric grids in wind, solar, batteries and electric grids, according to the International Energy Agency.

But Wright warned that he said the shift to renewables would likely be costly. “There has been a significant increase in wind and sun penetration everywhere, and prices have risen,” he said.

That's not always true. In Texas, electricity prices have fallen slightly over the past decade as wind and solar grow rapidly, and now supply more than a quarter of the state's power. The costs of wind turbines and solar panels have dropped sharply over the past decade. However, in some places like California and Germany, electricity prices have risen significantly as they have strengthened renewable energy use.

Some energy executives at the conference were more optimistic about renewable energy. John Ketchum, chief executive of Nextera Energy, the nation's largest producer of wind power, said renewables are essential to meet the growing U.S. electricity demand over the next few years, especially with a large backlog of new turbines that burn natural gas.

Renewables are “cheap and are available now,” Ketchum said. “If we look at gas as an example, we get a gas turbine and actually build it across the market, and we're really looking at it from 2030 onwards.”

In his speech, Wright skeptly criticized the Biden administration for slowing growth in natural gas exports. Last year, the energy sector suspended approval for new terminals exporting liquefied natural gas, saying it was concerned about the environmental and price impact of shipping more gas overseas. Despite the suspension, the US was the world's largest exporter of natural gas in 2024.

On Monday, Wright signed his fourth export approval since Trump took office, extending approval for the Delfin Terminal off the coast of Louisiana. He said the Biden administration's review of gas exports saw only a small impact on global emissions and domestic US prices.

On the topic of climate change, Wright said he didn't deny the planet's warmer and didn't call himself a “climate realist.”

However, he added that the increase in greenhouse gases from the combustion of fossil fuels, which raised the highest global temperatures in at least 100,000 years, is a “side effect that builds the modern world.”

“In fact, in the process of more than double the average life expectancy in the world, we have raised CO2 levels in the world by 50%, stripped almost every citizen of the world out of poverty and launched modern medicine,” he said. “Everything in life comes with trade-offs.”

Wright did not mention the shortcomings of climate change, including increased risks of climate, drought, flooding and species extinction. He has also not addressed the costs of adapting to a hotter planet, in developing countries alone, over the last decade alone.

Instead, Wright rebuked the UK for reducing greenhouse gas emissions faster than other wealthy countries, and by doing so he drove major industries overseas.

“I think it's sad and a bit ironic that once the UK's powerful steel and petrochemical industry was replaced by Asia, where the same product was produced with higher greenhouse gas emissions, loaded back into the UK on diesel-powered ships, and then loaded into the UK,” Wright said. “The end result is higher prices for UK citizens, lower employment, higher global greenhouse gas emissions, all of which are called climate policy.”

Wright said he is not opposed to low-carbon energy and supports the sophisticated forms of nuclear and geothermal power pursued by several US startups.

However, he said the administration's “all existence” approach to energy is likely not to reach wind farms, citing the opposition from some communities. President Trump opposed wind farms, saying it would cause cancer. The administration has halted approval of wind farms in public and federal waters and threatened to block projects on private land.

“Wind was chosen because it has a very poor record of raising prices and increasing public outrage, whether you're on a farm or in a coastal community,” Wright said. “So the wind is a little different.”

Trump administration's policies are unevenly popular among oil and gas producers. While many companies warn that Trump's tariffs on steel and aluminum could raise the prices of essential materials, such as pipes, used to line up new wells, the constant threat of tariffs on Canadian oil could raise the prices of refineries in the Midwest.

Wright avoided questions mainly about tariffs, saying “very early,” noting that inflation was low during Trump's first term.

Ivan Penn contributed report