For centuries, the famous pastoralists whose migration has shaped West and Central Africa, the Fulani people have been intrigued by historians, linguists and anthropologists. Where did they come from? How did their nomadic culture evolve? Currently, a groundbreaking genetic research by Fortes Lima et al. American Journal of Human Geneticsproviding fresh insight into the complex origins of Fulani, traced their ancestors to the ancient lost world, the green Sahara.

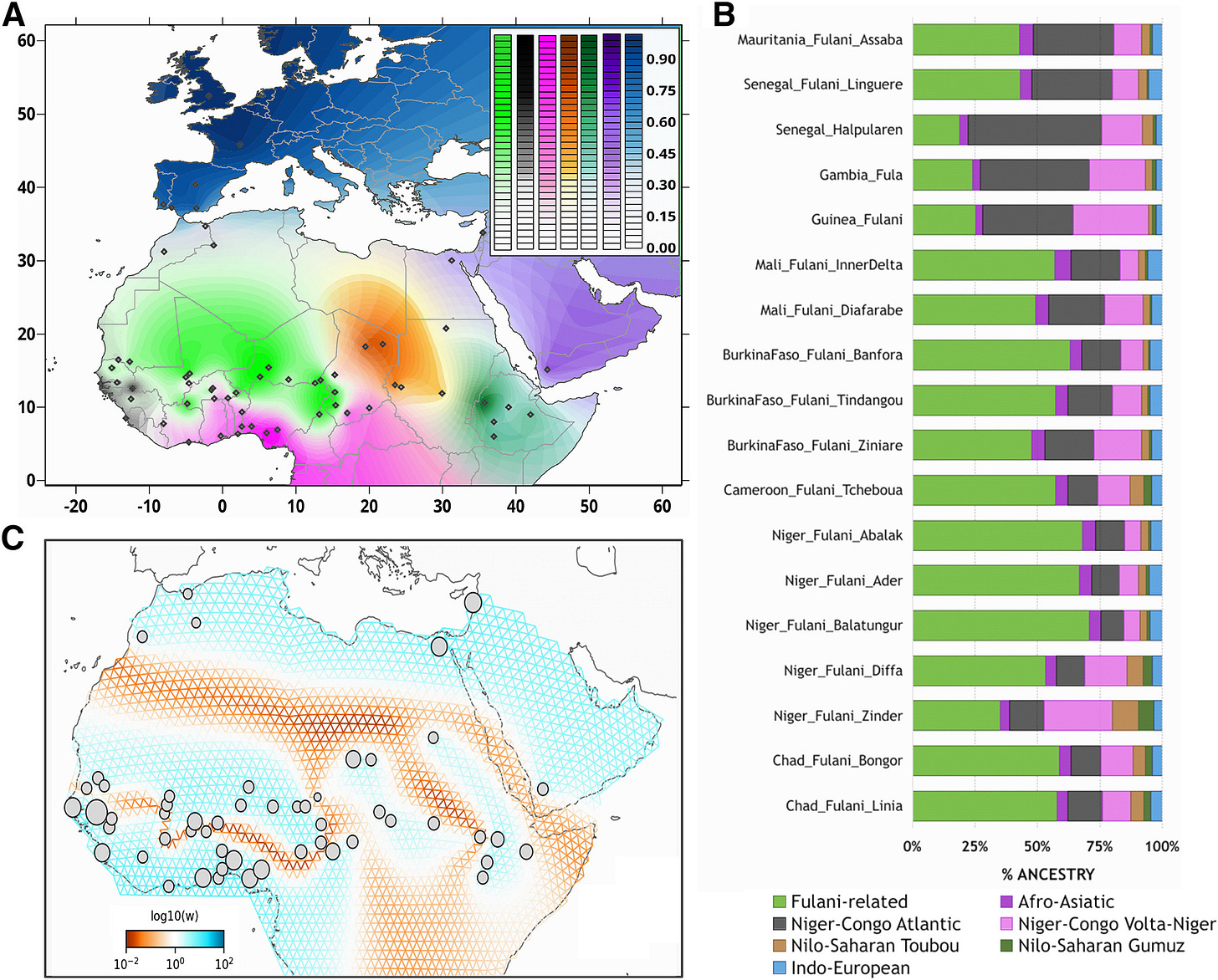

By analyzing the genomes of 460 individuals across an 18 Fulani population, the researchers discovered shared ancestral components that link them to early North and West African groups. The results tell the story of migration, adaptation, and survival in one of the world's most challenging environments.

“We have revealed genetic components closely related to all local Fulani populations, which are shared ancestors that may be linked to the beginnings of African pastoralism in the Green Sahara. It suggests that.

This study not only refines understanding of Fulani's history, but also challenges long-standing assumptions about African population genetics. It offers a glimpse into the genetic heritage shaped by climate change, trade networks and cultural interactions dating back thousands of years.

The Sahara was not always a vast, arid desert. 12,000 to 5,000 years ago, it was a fertile landscape of a network of lakes, grasslands and rivers, known as the Green Sahara. During this period, early idyllic societies flourished, swarming cattle and quickly moved across ecosystems engulfed by the desert, quickly moving forward.

This study suggests that today's Fulani ancestors likely originated from this green Sahara population. As the climate became dry and the Sahara transformed into a wasteland that kept people at bay, these early hermits were forced south to mingle with the local West African population. Their genetic traces remain in today's modern Fulani community.

“Comparison of Fulani and genetic data from ancient individuals has identified the presence of genetic elements in all Fulani populations associated with ancient North African groups.”

Unlike many other African groups, Fulani exhibit important genetic contributions from the Berber population in North Africa and traces of ancient Eurasian ancestry. This unique mixture has burned speculation about their origins for centuries. But as this study shows, the answer is much closer to home.

Beyond genetics, Fulani are bound by a clear cultural identity centered around cow herds, social stratification, and the strict ethical code known as Plaque. Their migration, trade networks, and interactions with other groups have shaped West Africa for centuries, affecting language, political structure and economy.

However, their genetic structure is not uniform. This study shows a prominent western-to-east slope in Fulani population, reflecting historic transitions and interactions with various communities. The Western Fulani groups showed stronger genetic ties to the West African population, and the East Fulani communities had evidence of interaction with Central Africa and sub-Niro-Saharan groups.

“Our analysis reveals genetic differences between local Fulani populations following the West East Klein, and a complex genetic history shaped by interactions with various local groups and various demographic events. I emphasized.

This genetic variation is consistent with linguistic and cultural differences between Fulani groups. While some communities are completely nomadic, others settle in agricultural villages and adopt new traditions while maintaining core elements of the herder's identity.

Despite their immeasurable historical significance, Fulani remains one of the least understood populations in genetic research. This gap represents a wider problem. Africa's population has long been underestimated in genomics, with most studies overwhelmingly focusing on European ancestors.

While this study illustrates an important step in correcting that imbalance, it also raises pressing questions about who benefits from genetic research. Many African populations, including Fulani, have little access to the scientific stories written about them. The research team worked in the community and gained informed consent, but broader concerns about data sovereignty and scientific inclusivity persist.

The authors of this study recognize this and call for greater cooperation with African researchers and institutions. Future research should ensure that genetic findings lead to concrete benefits for the community, whether in the form of improved healthcare, historical knowledge, and cultural conservation.

“Even though Fulani is a population group of over 40 million people, they are still primarily underestimated in genomics studies.”

Fulani has long been at the intersection of major migration and cultural change in Africa. Their genes carry echoes of the disappearing Sahara civilization, ancient cattle herders who once roamed the eco-friendly world, and merchants and nomads who navigated thousands of years of sub-Saharan trade routes.

This study provides compelling evidence that their history is even deeper and more complicated than previously imagined. It challenges a simple story about the “pure” African population, revealing the complex tapestry of migration and adaptation that shaped human history across the continent.

As older DNA studies emerge, Fulani's stories, as well as the stories of deep genetic history of Africa, become richer. But one thing is certain: Fulani is not an isolated anomaly. They are the living testimony of the vast, interrelated human journey that has been unfolding in African soils for tens of thousands of years.

Fortes-Lima et al. (2025) We conducted extensive population studies of Fulani and found genetic differentiation along the west-east Klein across the Sahel. Their findings highlight mixed events with other African populations and deep genetic links to ancient North African groups.

📄 Quote: Fortes Lima, California, Diaro, me, Janowshek, V. , Charney, V. , and Schrebusch, C. (2025). Mixed with population history of the Fulani people of the Sahel. American Journal of Human Genetics.

🔗 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2025.04.012

Vicente et al. (2019) We investigated genome-wide adaptations of Fulani nomads focusing on the persistent properties of lactase. Their research suggests that historical selection pressures associated with idyllics played an important role in shaping genetic makeup.

📄 Quote: Vicente, M., Priehodová, E., Diallo, I. , & Podgorná, E. (2019). History and genetic adaptation of Fulani nomadic populations: genome-wide data and inferences from persistent characteristics of lactases. BMC Genomics, 20(1), 1-12.

🔗 doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6296-7

D'Atanasio et al. (2023) Whole genome data were examined to track the last green Sahara-era genetic echoes of Fulani and Sahel populations. Their findings suggest that Fulani's ancestors may have been Sahara cattle herders.

📄 Quote:D'Atanasio, E., Risi, F., Ravasini, F. , & Montinaro, F. (2023). The last green Sahara genomeecho of Fulani and the Saherians. Current Biology.

🔗 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.09.012

Hassan & Underhill (2008) We analyzed Y chromosome variation among Sudan groups and demonstrated that Fulani possess distinct genetic structures influenced by language, geography and historical migration.

📄 Quote: Hassan, High, Underhill, PA (2008). Y-chromosome variation between Sudan: restricted gene flow, language agreement, geography, history. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 137(2), 168-174.

🔗 doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20876

Chernie et al. (2006) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was investigated among Fulani nomads and revealed significant differences compared to sedentary populations in West Africa.

📄 Quote:Jenny, V. , Hajek, M., Bromova, M., chmejla, R. , & Diallo, I. (2006). Their genetic relationship between Fulani nomadic mtdna and adjacent sedentary populations. Human Biology, 78(1), 9-22.

🔗 doi: 10.1353/hub.2006.0024

These studies help contextualize current research by highlighting the complex migration patterns, genetic adaptations, and historical interactions that shaped Fulani people.