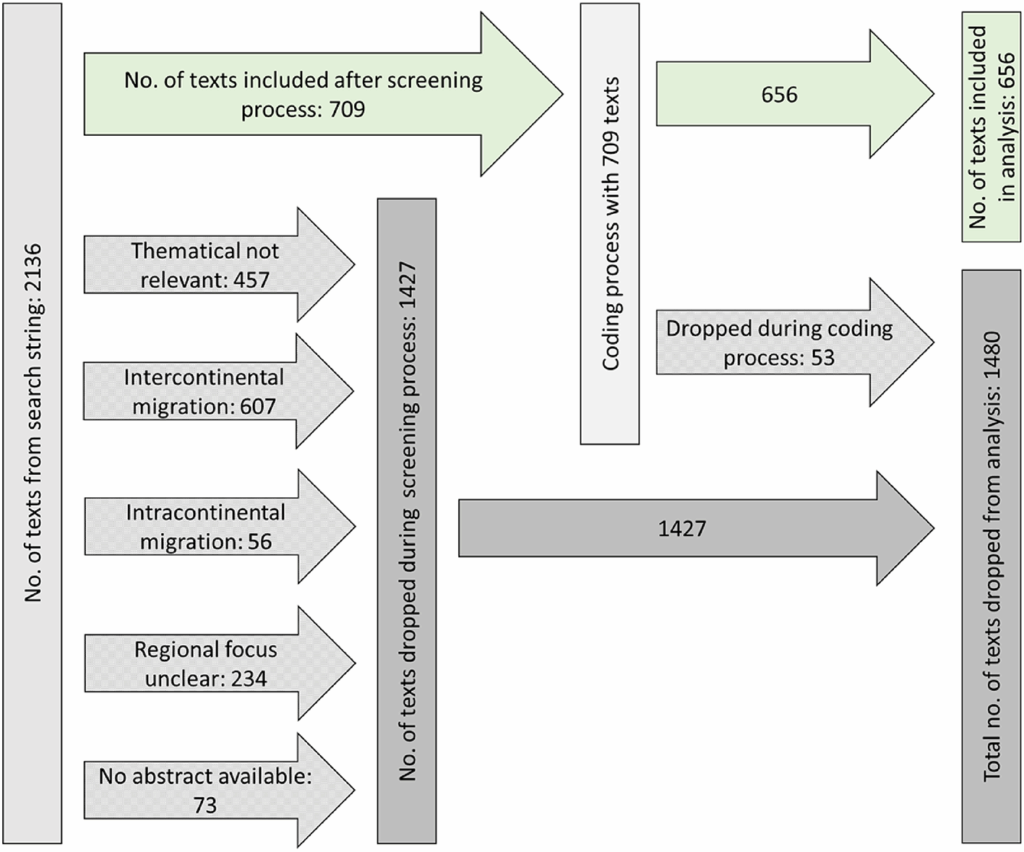

This section systematically presents our results. It is based on the dimensions mentioned in the introduction and illustrates how they intersect. The presented and interpreted results are the basis for the next section where research gaps and future research avenues regarding migration are discussed in more detail.

R1 Development of publications over time and thematic and regional foci

As a first indication on the development of research on ‘migration in West Africa’, Fig. 2 shows the number of publications for each year from 1958 to 2021.Footnote 11 With less than 5 publications per year, the field did not receive a lot of attention until 1986. Afterwards the number of annual publications increased moderately and remained at a low level with some fluctuations (3–9 publications per year) until 2001. 2002 marks the beginning of a strong and continuous increase with up to 52 publications on the topic in 2021. Our finding, that the number of publications on migration in West Africa picked up around the 2000s, is in line with a general trend in migration studies (see Dahinden, 2016; Scholten et al., 2022). While Dahinden (2016) points to the institutionalization of migration studies as a discipline since this time, Scholten et al., (2022) explain this trend with the general diversification of the field. Beside an increasing variety in research locations, the groups studied and methods applied, the diversification in migration studies is reflected by the growing number of its topics. This explains the emergence of certain themes in our study (such as Health, Social relations/Family & Affinity and Climate change) only after the turn of the century. In addition, at this time further developments in technology have led to an overall increase in scientific publications through the increased use of the internet and forms of digital communication. The growth of migration studies is further exemplified by an increasing self-reflexive awareness of its concepts and approaches (Scholten et al., 2022), e.g. transnationalism and moving beyond national borders as “naturally given entities” within the discipline (Wimmer & Glick Schiller, 2002:221). Hereby, the emergence of reflexive migration studies has also contributed to the growing inclusion of perspectives and issues beyond the Global North, including West Africa, though knowledge production in the field remains uneven (Piccoli et al., 2023).

Number of publications per year (1958–2021)

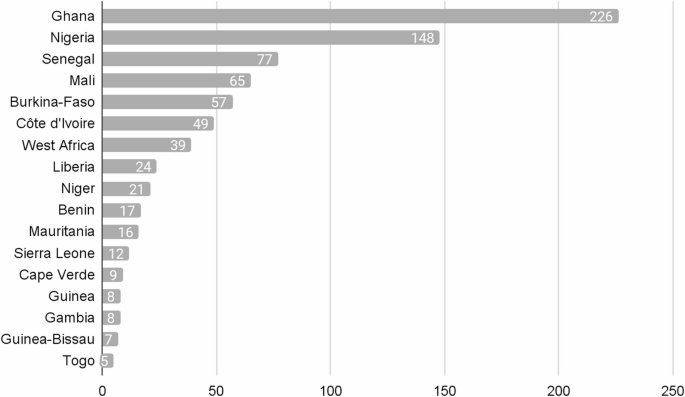

Concerning geographic focal points, Fig. 3 shows the number of studies in which migration in or from a country was investigated. Ghana (226), Nigeria (148), Senegal (77), Mali (65), and Burkina Faso (57) were by far the most frequently mentioned while Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau and Togo were named in less than ten publications each. These differences remain relatively stable over the examined period. Possible explanations for the relatively high share of articles concerning Ghana and Nigeria are multifarious. They include (a) their historical importance as countries of migration, (b) their economic significance, (c) political stability and security (Ghana), (d) a comparatively very large population (Nigeria, 213 million) and (e) English as a vernacular due to their colonial history (Falola, 2024; Teye, 2022). All of which build fundamental prerequisites for (international) research and field access. The high share of affiliations from the Global North that we have identified for publications on Ghana and Nigeria (see R3) endorses the stated assumptions. Moreover, the majority of publications affiliated with West African institutions also originate in Ghana and Nigeria, which points to a relatively strong national academic landscape and may further explain the concentration of migration research on the two countries.

Frequency of country codes

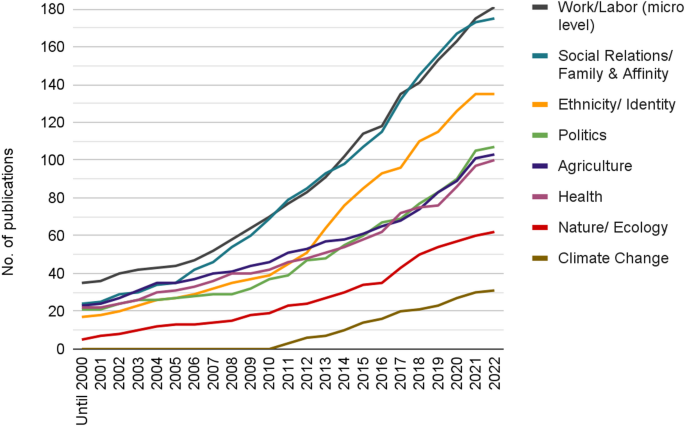

Of the thematic categories, Work/Labor (micro level) (181), Social relations/Family & Affinity (175), Ethnicity/Identity (135), Politics (107), and Agriculture (103), received the most attention. Figure 4 illustrates the development of selected categories since the year 2001. Five of the selected topics exhibited a comparable number of publications up to the year 2000 (ranging between 35 and 21). From 2001 onwards, three distinct publication clusters can be identified: (1) Work/Labor (micro-level) and Social Relations/Family & Affinity experienced the most significant increase in publications, with Ethnicity/Identity showing a similar growth, though at a smaller absolute volume. (2) Politics, Agriculture, and Health demonstrated a moderate increase in publications, with similar trends across these topics. (3) Nature/Ecology and Climate change saw the smallest increase, with Climate change being first explicitly addressed in the literature in 2011 with up to four publications per year, totalling 31 publications until 2022. The more general topic of Nature/Ecology (62) has been dealt with for much longer (since 1988) than Climate change.

Number of publications for selected topics over time

While the most relevant thematic categories have been researched in a relatively similar frequency across the most-studied countries, there are some exceptions (proportional to the total number of publications associated with the respective country). Table 1 presents the 12 most important topics (more than 40 codes each) itemised by how often they are mentioned in regard to each of the five most frequently mentioned countries. Politics has been covered disproportionately often in the context of Mali (23%) and Senegal (21%) while Agriculture is a comparably strong topic in migration research in Burkina Faso (25%). In comparison, Health stands out as a focal point for Ghana (23%) and makes up a large share for research on Senegal (19%), while Gender makes up a large share of research regarding Mali (17%).

R2 Aspects and forms of migration in relation with topics (over time)

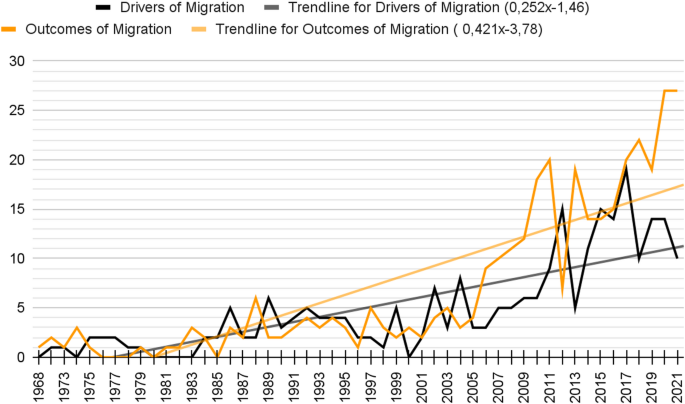

Further, we found that research looks rather at the outcomes of migration (351) than at the drivers of migration (250). Of these, only a relatively small number of studies (15) highlighted both. The studies focussing on the outcomes of migration are the ones that deal to a large extent with the area of destination (172), rather than with the area of origin (96). The ones that focus on migration drivers mainly look at the area of origin (82) than at the area of destination (45). Figure 5 illustrates the following changes over time: up to the early 2000s, both the drivers and the outcomes were emphasised similarly with only minor and fluctuating differences. From 2005 onwards, studies began to primarily emphasise migration outcomes while the number of publications studying the drivers grew more moderately. From 2010, the overall stark growth in both categories came with drops in single years: Regarding the sum of the texts on the drivers, the peaks in 2012 (15) and 2017 (19) were followed by drops in 2013 (5) and 2018 (10). Whereas the sum of texts on the outcomes of migration shows a steadier rise after single peaks in 2011 (20) and 2013 (18), interrupted by a drop in 2012 (7). After that, the figures for the outcomes tend to be higher with fewer fluctuations while there is a clear peak with 27 texts in 2020 and 2021 each.

Number of texts emphasizing drivers and outcomes of migration since 1968 (For this figure, 1968 was chosen as the starting year due to lack of sufficient data for previous years)

Another set of categories that can be considered with the drivers and outcomes of migration are the topics of research. Table 2 shows the frequency of each thematic category depending on the context of the study. In our findings, we further came across discrepancies when considering the thematic focal points in combination with research perspectives. While some topics have a similar relative share (Social relations/Family & Affinity, Work/Labor (micro level), Politics, Urbanization, and Education), other topics are more often associated with either outcomes or drivers of migration. The largest differences are found for the categories Health (23% outcomes/5% drivers), Nature/Ecology (5%/15%), and Climate change (2%/10%). The categories concerned with the climate crisis and environmental aspects have proven to be mentioned disproportionately more with the causes of migration. The difference regarding the perspective on migration in the thematic categories Nature/Ecology and Climate change may originate in the recent academic and policy debates on so-called ‘environmental refugees’ which apparently increase academic interest in the causes of migration in this context (Epule et al., 2014). This matches our findings, as, as mentioned, the category Climate change has only been assigned to articles from 2011 onwards while Agriculture and Nature/Ecology have been researched for longer – although to a lesser degree in recent years. Potentially, the beforehand thematised natural events were consequently discussed in terms of their effect on West African agriculture and migration movement resulting from either. Recently increased media reports concerning ‘climate refugees’ (Høeg & Tulloch, 2019) strengthen this assumption. However, as a number of studies (e.g. Aufenvenne & Felgentreff, 2013; IPCC, 2007; Piguet et al., 2018) have shown, the relationship between climate and migration is more complex than the notion of ‘climate flight’ suggests, and migration is always linked to various social, economic and/or political factors that promote or inhibit migration. Regarding the topic of climate change, it is to mention that its appearance in the articles only after 2011 can be attributed to a general increased setting of geopolitical priorities on climate topics in the past years due to a greater awareness of the climate crisis. This further may have led to an epistemological shift in migration studies towards a greater awareness of threats and changes in our living conditions and have set ground to an increased focus on consequences of climate change on migration and mobility.

Regarding the research site, we found that most studies focus solely on the area of destination (212), compared to 163 studies that focus on the area of origin; in 21 additional cases, research dealt with both areas. Most research focuses on rural-urban migration (127), with a total of 173 texts considering exclusively urban areas of destination, while rural areas of destination play a rather minor role (82). Among the overall 184 texts taking urban areas of destination into consideration,Footnote 12 the category Work/Labor (micro level) (64) is most present, followed by Urbanization (54) and Social relations/Family & Affinity (44). Work/Labor (micro level) (76), Social relations/Family & Affinity (64) and Agriculture (59) were the most prominent categories in research considering rural areas of origin. This indicates a widespread separation of migration localities in research practice, although 132 texts in our study contain aspects that connect migration localities of origin and destination, e.g. by referring to remittances. 45 of these 132 texts deal with the drivers and significantly more (84) with the outcomes of migration. With reference to the concept of translocality, we found that only one of the 132 publications applied a deliberate translocal perspective and hence moved beyond the separation of interlinked places in migration research. In fact, the overall average (and median) of texts dealing with aspects of translocality lies at 16%. This rather low figure underlines that research on migration West Africa is predominantly based on approaches to study migration in social and spatial isolation at either the area of origin or destination and not as an interlinked, space-spanning phenomenon. However, since 2007, the number of texts that consider aspects of translocality is growing. Since then, 20–35% of texts take spatial interlinkages at least implicitly into account. Based on this, we draw two main conclusions from our results: (i) Translocality is still a rather new and not yet well-established concept in migration research in West Africa. (ii) However, it is an emerging and promising paradigm that has the potential to overcome the problematic division of migration areas of origin and destination (and possibly other connected places) by stimulating research to take space-spanning interconnectedness of migration localities into account.

The relevance of a translocal approach is furthermore visible in relation to additional results from our study. Our data suggests the continued prevalence of two narratives regarding the direction of migration and the questions with which research approaches migration. Due to the strong focus on rural-urban migration, we conclude that the presumption within research that migration mainly occurs from rural to urban areas (Dick & Schraven, 2021) is still persistent. In combination with a stronger focus on the outcomes of migration (351 entries in our study), which have more often been concerned with the places of destination, the decades-old criticism of the so-called ‘urban trap’ of researchers, prominently raised by Chambers (1983:7), comes to mind. Chambers (1983) discusses the preference of scholars to conduct research mainly in the convenience of a city rather than in the structurally often less equipped and well-connected rural areas. This trend is visible in our findings, which indicates that research is to a large extent concerned with urban challenges, whereas aspects of rural development fall shorter in comparison. However, as an exceptional case, climate change implications are strongly linked to rural settings with little emphasis on urban areas. As a consequence from these local disparities, migration research in West Africa that balances its focus between urban and rural locations would probably help to diminish both research gaps and the overemphasis of certain location-topic-constellations. Still, this does not automatically help to overcome separated studies and isolated findings. From a translocal perspective, it is rather important to link relevant localities in the research approach, e.g. by multi-sited approaches (Marcus, 1995), and hence contribute to a coherent, space-spanning study of migration phenomena.

As far as the type of migration is concerned, though it was often impossible to identify the type of migration in the studied abstracts, we found that Unilinear migration (101), Circular migration (54), and Expulsion/Displacement/Flight (33) are the most common types of migration that are researched. Regarding the people in focus, most studies deal with migrants (405) compared to non-migrants (87). Further demographic differentiations, such as age or gender of the people in focus, are not possible as most abstracts did not disclose this type of information.

Apart from the discussed interrelations, other categories did not yield enough insights to derive robust trends or even tendencies. However, in some cases, it is particularly insightful to analyse the reasons and implications for this absence. A notable observation is the lack of migration classifications (such as circular, unilinear, seasonal, etc.) in the articles’ abstracts. Various reasons may account for this and include an authors’ notion that the designation of the action as migration is sufficient and that there is no need to further differentiate the exact type in the abstract, or that an exact categorization of the studied migration practice is difficult to identify. In any case, the lack of classifications points to general conceptual issues to differentiate forms, types, or flows of migration. In line with the earlier-mentioned criticism of nation-states-centred concepts (Favell, 2003), Dahinden, (2016) highlights weaknesses in categorizations or typologies of migration: while some would not exist without the ordering unit of a nation-state (internal/international), others may as well intersect, overlap, or fluidly alternate (Talleraas, 2022). Other scholars highlight the definitional inaccuracy of the term ‘migrant’ itself, mostly in distinction to or as inclusive of ‘refugee’ (ibid.). Carling (2017:4), therefore, calls for an “inclusive meaning of ‘migrants’ as persons who migrate but may have little else in common. In that way, we respect both the uniqueness of each individual and the human worth of all.” These criticisms in conjunction with our data show that a reflexive perspective is important to draw attention to insufficient conceptualisations and categorisations in migration research and, at best, to contribute to their actualisation to enable a differentiated view of migration and mobility processes.

R3 Affiliations

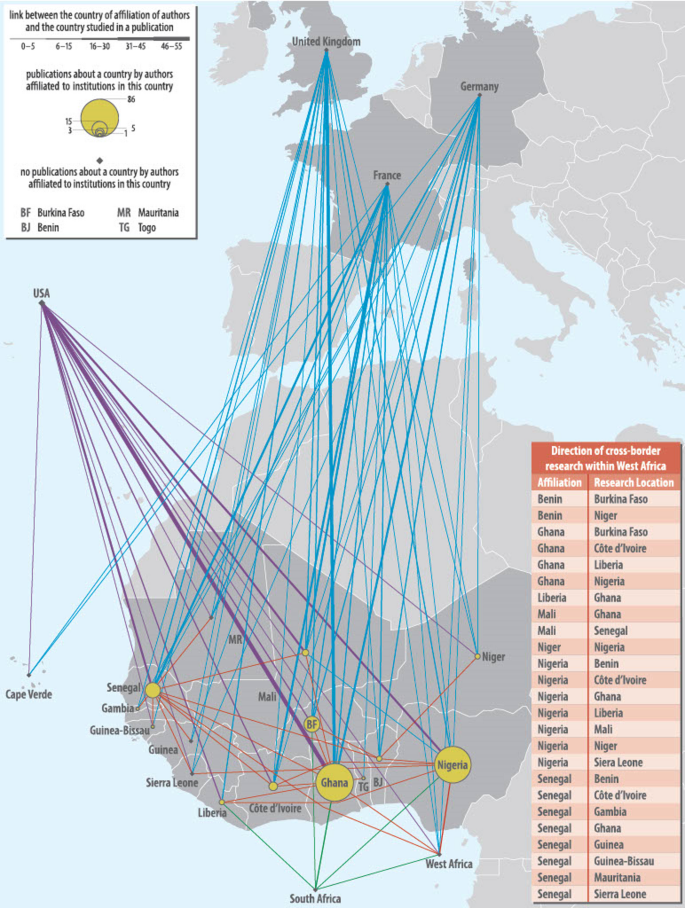

Moreover, we took a closer look at the affiliations of the authors of the publications and related them to thematic and regional priorities. Overall, 1321 codes were assigned to categorise the authors’ affiliation(s). Most affiliations are found in the USA (215), Nigeria (181) and Ghana (176). Among the West African countries, Senegal (30) and Burkina Faso (23) follow as number three and four with a large gap to the leading two. Overall, West African affiliations account for 487 codes, while 518 affiliations are attached to Europe. Of these, 325 affiliations are located in the former colonial powers: the UK (137), France (104), Germany (82), and Portugal (2). Hence, most researchers publishing on migration in West Africa are not affiliated with institutions based in (West) Africa. In addition, the researchers affiliated with institutions in (West) Africa mostly published about the countries matching their affiliated institution’s nationality. An exception is South Africa where 30 publications on West African migration originate, which may be explained with the well-established academic system in the country that allows for broader research horizons and foci (Cloete et al., 2015).

Besides the total number of affiliations, we granted special attention to the first author’s affiliation. Out of 1321 coded affiliations, 633 are labelled as “first author”, accounting for 48% of the total assigned codes regarding affiliations. The relative shares of first authorship among affiliations located in the three regional foci ((West) Africa, Europe, and USA) differ. 40% of West African affiliations are also the first authors, while Europe and the USA have a ratio of 52% and 56% respectively.

Connections between the most important countries of affiliation and research locations

Furthermore, we investigated whether there is a connection between the affiliations and the researched country, illustrated by Fig. 6. The findings show that in the case of France and the United Kingdom, research concentrates on their respective former colonies. Strong connections exist between France and Mali, as well as between the UK and Ghana. While Ghana also attracts significant research attention from German research, the country is generally an important site of research for researchers based outside of West Africa.

Our results reveal the dominance of research conducted by authors affiliated with institutions based in the Global North, while publications affiliated with West African countries are mostly also conducted in the same country. Thus, the concentration of West African affiliations with Ghana and Nigeria explains the high amount of research articles associated with the two countries. The relatively large number of European affiliations, British and French in particular, indicates an ongoing connection and access based on the colonial past.

From a reflexive migration studies point of view, the dominance of the Global North is problematic for reproducing power imbalances in knowledge production. For example, the reference to the above-discussed analytical topics Nature/Ecology and Climate change and the category of demography reveals how these linkages shape agenda-setting in migration studies. Regarding the environment-migration nexus, Piguet et al. (2018:14) state: “Northern countries appear very interested in sending researchers and funding studies to document migration (…) in the South”. Their results reveal that most research conducted on environmental migration is funded and conducted disproportionately more by Northern countries – while the research sites are more often in the Global South (ibid.). Regarding the topic of women’s migration in West Africa, colonial policies of promoting men’s labour migration to mines and plantations within the colonies formed the basis for the longstanding academic focus on men’s spatial mobilities and their impact on home communities and households. Migrant women, on the contrary, were widely absent in academic engagements with migration (Ungruhe, 2018; Setrana & Kleist, 2022).

The problem of this agenda-setting is that it further translates into an authority of interpretation that can, according to Held (2019), be translated into the strong dominance of Western paradigms, research approaches, and methodological frameworks. All of which are based on already existing ontological, epistemological, and axiological assumptions rooted in the ongoing Western dominance over knowledge creation and interpretation (ibid.). With respect to both the environment-migration nexus and women’s migration, this has contributed to the dominant problematic paradigm of ‘climate refugees’ and, respectively, the assumption of women as either sedentary or followers of men as discussed above. When talk is of tens of millions ‘climate refugees’ in the coming decades (see Jakobeit & Methmann, 2012), it is often about people seemingly fleeing from Africa to Europe. Hereby, the narrative turns the problem of harsh climate futures in the Global South into an alarming immigration scenario for the Global North while their consequences for the people and societies in the Global South itself receive much less attention (Mathis & Schraven, 2015). Similarly, the neglect of women migrants in academic research framed women’s spatial mobilities as outside the norm and, hence, contributed to problematizing women’s migration as risky, harmful and a violation of social norms. Hereby, it rather transported Western views of gender roles and practices rather than mirroring local conditions in West African settings (Ungruhe, 2018; Setrana & Kleist, 2022).