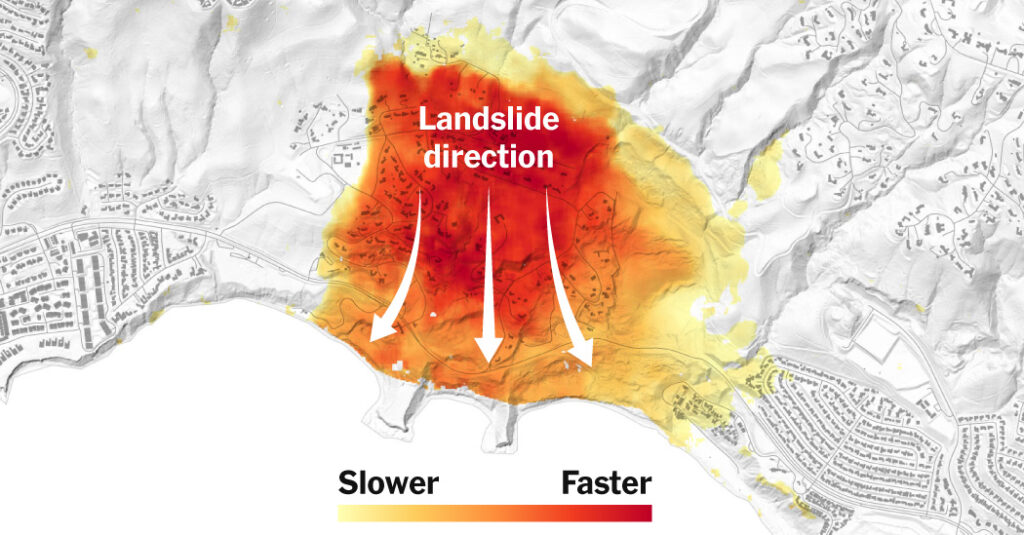

Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Data from September 18th to October 17th, 2024

A series of landslides creeping towards the sea along the glowing coast of Southern California, transforming the wealthy community of Rancho Palos Verdes into a disaster zone.

New data from NASA planes illustrate the growing threat of these slow-moving landslides that are destabilizing roads and utilities and other homes, businesses and infrastructure. Researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Institute documented how landslides, which have almost doubled the area since the state mapped in 2007, were pushed westward.

Landslides have also skyrocketed in recent years. A month-long aerial radar image taken by NASA in the fall revealed that land on the Palos Verdes Peninsula had slid four inches into the sea each week between mid-September and mid-October. Before that, the city's report showed more than a foot of movement each week in July and August.

Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The current boundary includes areas where landslides travel faster than 1 centimeter a week between September 18th and October 17th, 2024.

Los Angeles County slide blocks, known as the major Portuguese Bend landslide complex, were revitalized in 1956 after road construction destabilised the former Dormas slope. For decades, it slid just a few inches each year. However, the heavy rains of 2023 and early 2024 accelerated that movement, leading Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a state of emergency, citing “conditions of extreme danger to the safety of people and property.” Ta.

The Rancho Palos Verdes home began to collapse in June and August 2023. The street is torn. The walls are varied, the floors are cracked and open, revealing the dynamic earth below. The fallen power lines associated with the slide began fire in August. The $42 million buyout program helps property owners voluntarily sell and relocate, but homeowners' insurance typically doesn't cover landslides.

The coastline spreads with landslides on the beach of Rancho Palos Verdes.

Lauren Elliot of the New York Times

Damages in a residential area in Rancho Palos Verdes in August.

Lauren Elliot of the New York Times

Mitigating such disasters is extremely expensive. By the end of this fiscal year, the city said it would spend almost 90% of its general fund management budget over $35 million to deal with landslides. This includes the installation of 11 wells that worked to pump 145 million gallons of groundwater, which could further destabilize the slopes. This investment has resulted. Landslides slowed on average about 3% between December and February thanks to a lack of wells and rain, the city said.

Slowly moving slides are common all over the world, especially in California, where hundreds of animals are mapped to coastal mountain ranges. These slides, which usually move at a slow pace, can almost halt during a few dry summer months, before wet winters cra again.

However, last summer, the landslide complex in Rancho Palos Verdes showed strange behavior when it couldn't be slowed down. The best speculation of why it is linked to a very wet 2023 is said Alexander Handwager, a research scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Institute, who has been studying the behavior of slow moving landslides for over a decade. Usually caused several tens of meters underground, they remain a continuous field of research.

“In all that we know,” said Dr. Handwerger.

Last week, other parts of Los Angeles County faced additional landslides. This is facing a landslide that runs at meters per second rather than centimeters per week and moves quickly. The National Weather Service in Los Angeles announced a stream of debris after burns (a warning like mud, rock and wood tangles starting with burn scars) ahead of heavy rain on Thursday. Last month, the Los Angeles district, which was scorched by wildfires like the Eton and Palisade fires, faced the greatest dangers as those streams hit businesses and homes in Southern California.

However, slower landslides like Rancho Palos Verdes are more predictable. They ooze out, not race. They usually require a rainy season rather than a single storm to accelerate. And it's very rare for them to suddenly collapse or slip in a devastating way.

Luke McGuire, an associate professor of geomorphology at the University of Arizona, said the reason for causing such a sudden catastrophe is unknown. He pointed out one of the few known examples of such events. In 2017, a landslide in Big Sur at Mud Creek gave way after eight years of steady skiing. Over 65 feet of rock and dirt covered a quarter mile of Highway 1, a scenic drive that winds along the California coast.

Experts say the city of Rancho Palos Verdes will probably not experience such a sudden event. “I can never say this, but it's very unlikely that this will fall into a catastrophic movement stage,” says Dave Petry, a landslide expert who collects global landslide data for the American Geophysical Union. I did. “It will probably continue to cause significant property damage, but there's not a particularly high risk of things slipping into the ocean and taking it with you.”

A 2019 natural survey by Dr. Handwager showed that Mood Creek landslides could have been caused by the transition from drought to record-breaking rainfall. In the world of warming, the rise in extreme rain events could lead to more landslides faster, according to research.

It is also possible that more landslides will appear on slower moving slides from hibernation.

“Rainfall under climate change can cause landslides,” Dr. Petry added that there are a huge number of dormant landslides around the world with this possibility.