Flash floods have been causing chaos across the country recently. In New Mexico. North Carolina. And with many accounts issued emergency warnings from last week's floods, the National Weather Service acted appropriately.

But weather services personnel have been affected by the Trump administration's cuts across the federal government. Some experts say future predictions and warnings can be painful.

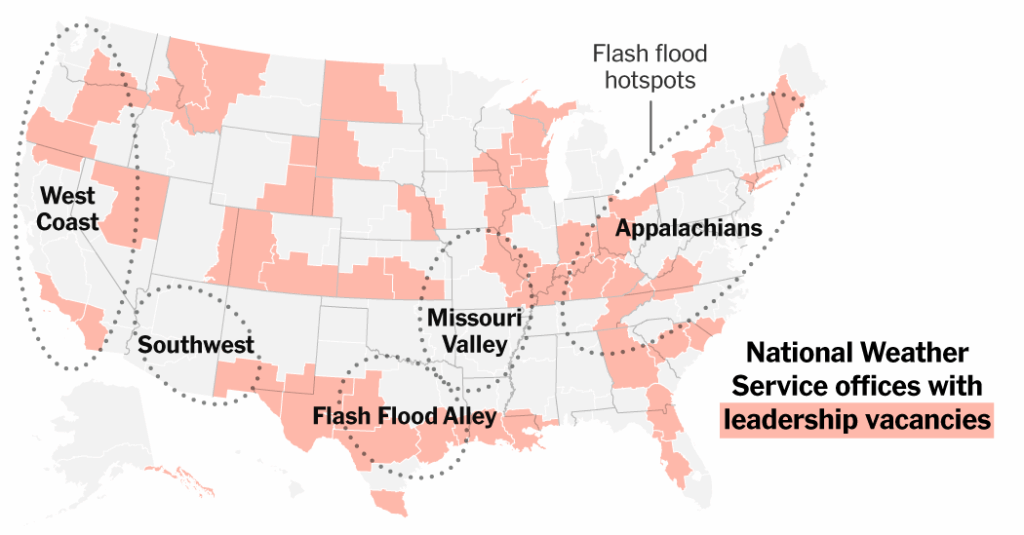

An analysis of the National Weather Service vacancy found that more than a third of offices that are particularly vulnerable to gun floods did not fill in one or more of the three senior leadership roles, including the Chief Meteorologist.

According to the Meteorological Bureau's staff list, the Houston-Galveston office spans an area that frequently sees hurricanes but also known as the “slash waterways,” but currently there are no chief meteorologists, chief hydrologists or warning-adjusted meteorologists.

The Austin San Antonio office is one of the areas that was hit hard by weekend floods that killed more than 120 people in April due to the lack of a permanent warning adjustment meteorologist, and is usually a post that oversees the Meteorological Bureau's contacts with local emergency officers and others. The San Angelo office, the other office, does not have a chief meteorologist.

It was an impressive effort for weather service staff to push out flash flood warnings three hours before a deadly rapid hit in Texas.

Still, the overall lack of staffing “will weaken agents and weaken their preparations,” he said. “The longer these vacant seats, the more stressful these offices are.”

Leadership vacancy has more than doubled

Neil Jacobs, the election in which the Trump administration will lead NOAA, faced doubts about staffing concerns during a confirmation hearing on Wednesday. The National Weather Service is part of an agency led by Jacobs.

“NOAA has lost at least 1,875 employees, totaling 27,000 years of experience and institutional knowledge, and has over 3,000 vacant staff positions at the worst times,” said Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota.

“If confirmed, we want to make sure the staffing weather services office is our number one priority,” Jacobs said.

NOAA communications director Kim Doster said the agency confirmed that additional staff were on duty during the floods in Texas. “All forecasts and warnings were issued in a timely manner,” she said.

Agency officials also said that the agency will use short-term allocations and reallocations to fill positions in field offices where its biggest needs are and that “mission-critical field positions” will be promoted immediately despite the overall employment freeze.

Flash floods caused by heavy rainfall are one of the most deadly extreme weather events. They are complex events and are difficult to predict. To send warnings and alerts, meteorologists need to consider the many supercomputer-generated weather models that predict the future to calculate data about current weather.

This presents a specific challenge for federal weather forecasters in some countries where rapid-moving flooding is prone to them. Decades of flood data refer to “hot spots” of these flash floods. It is usually an area that includes mountain streams and rivers that can easily overrun following extreme rainfall.

And as the planet warms, flash floods are predicted to become more severe, or, as researchers say, “flashing” and, devised by scientists, calculates and compares the rate and severity of the flood. The more flashy the flood, the faster the water will rise, and there are greater dangers it could possibly bring, and perhaps even overwhelm the dam and other stormwater defenses.

A team of scientists at the University of Oklahoma, who tracked decades of data from river gauges and other sources, found that if climate change continues unabated, more than 10% of flooding becomes flashy in parts of the country, such as the southwest.

Smaller rivers and streams tended to be the most common as they swelled rapidly after heavy rain and had little dams or other infrastructure to stop deadly flooding.

In the face of these changes, National Weather Service has seen network-wide reductions. Two or more of the top positions are vacant in the weather services offices that oversee Oregon and parts of California, Texas, Ohio and Kentucky, all within flash flood hotspots.

Overall, as of July 7, there were over 70 vacant leadership positions in Meteorological Bureau offices across the country, compared to about 30 at the same time last year, according to staff data.

The manager said the manager was bringing forecasters from other offices to fill the shortfall. Managers are particularly concerned about the Houston office. The Houston office lacks an entire top tier of managers and borrows Chief Mesmetol scholars from other offices. The Southern Regional Office, which oversees the 10 states, also does not have any major officials, including local hydrologists.

The vacancy also exists at the top post of 13 Regional River Forecast Centres, which are responsible for issuing guidance on flash floods from local weather offices. Two of the three top posts are open at the Changhassen, Minnesota center. There is one top post in the Pleasant Hill, Missouri office, which oversees the Missouri Basin.

Vacancy goes beyond flash flood hotspots. Some offices had missed the technicians responsible for maintaining wireless communications, another said, and relied on nearby offices to fill the gap.

Rick Spinrad, NOAA administrator under President Barack Obama, said he was worried about the service's ability to respond to events, especially when hurricane and wildfire seasons begin to reach their peak.

In particular, local weather services are expected to run 24 hours a day, and could be tasked with sending alerts in the middle of the night as Austin staff were forced to do so in the recent Texas flash flood. “It could be Cleveland, it could be Spokane,” he said. “I don't know how we can reduce staffing and hope to have the same quality and timing.”

The Trump administration's plan to eliminate NOAA's research division could mean work on forecasting and improving tools would stall, he said. “It ensures we never see improvement,” he said.

Hatim Sharif, professor of civil and environmental engineering at San Antonio, said: That's especially important for flash floods, which people tend to underestimate.

Last month, 13 people died in San Antonio after trying to pass through a fast-flowing street. “All of them washed away,” he said.

The public outreach was Paul Yura, a warning-adjusting meteorologist at the National Weather Service's Austin office before he retired early in April, local news outlet KXAN reported.

He spent many of his career warnings about the dangers of flash floods in the area. “We've worked on many different events that we didn't expect heavy rain overnight, but one thunderstorm will throw away all this rain and get a big flash flood,” he told local environmental officials in one November talk.

Unable to comment on this article, Yura retired two months before the recent flash flood in Texas. His position remains unfilled.