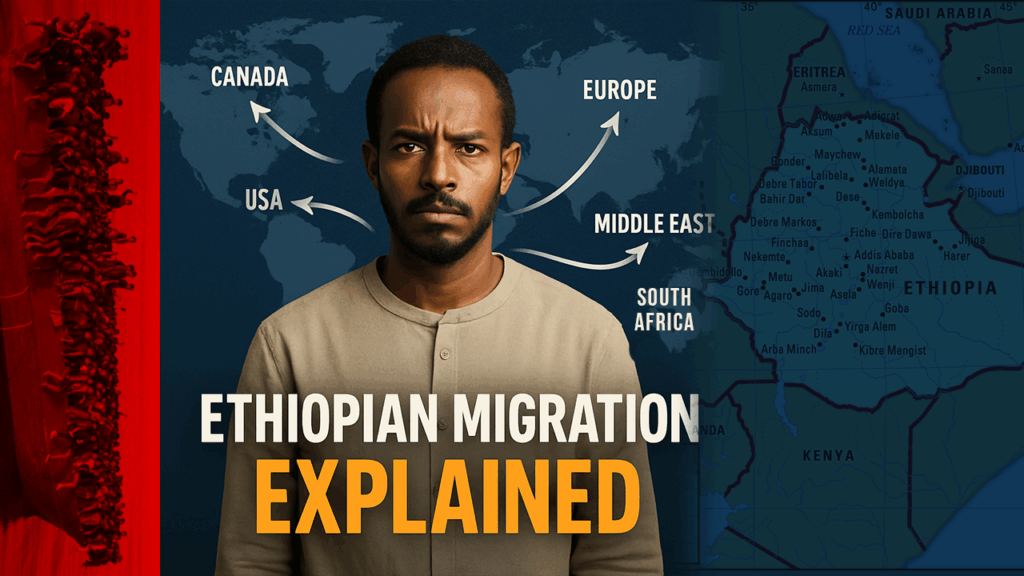

Ethiopia's migration patterns are shaped by a combination of both past and present political, social, economic and environmental factors, with approximately 250,000 Ethiopians migrating annually. For decades, Ethiopians have moved across borders, across regions and internationally. They seek better opportunities and evacuate political instability or simply escape harsh living conditions. Today, Ethiopia's migration continues to evolve, presenting new challenges and opportunities, especially as people seek foreign labor and flee conflict.

Before the 20th century: Internal movements and local connections

Historically, Ethiopia's migration was primarily internal, with a diverse ethnic group engaged in agriculture, trade and pastoralist seasonal movements. This kind of internal mobility has long been a hallmark of Ethiopian society.

Furthermore, Ethiopia's strategic location near the Red Sea promoted regional interactions. Ethiopians participated in trade, religious pilgrimage and cultural exchanges with neighbouring regions, including the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan and Egypt. These movements contributed to a rich tapestry of cultural and economic ties in the Horn of Africa.

Early to mid-20th century: The rise of international migration

The country has experienced extreme political turmoil, recurring droughts, hunger and catastrophic civil wars. Since the mid-1960s, Ethiopia has witnessed massive droughts and hunger, often encountering forced internal resettlement and “village” programs that often moved rural communities.

In the 20th century, international migration from Ethiopia became more prominent. Ethiopian students and intellectuals sought educational opportunities overseas, particularly in the US and Europe. Emperor Haile Ceracy's government helped many students study in the Western countries and encouraged the establishment of Ethiopian diaspora communities in cities such as Washington, DC and Los Angeles.

During Hale Theracy's rule (starting in 1930), immigration was minimal, and mostly involved urban elites seeking education overseas. Between 1941 and 1974, approximately 20,000 Ethiopians left as students and diplomats, according to the Institute for Immigration Policy. Most have returned to take on the role of government, but despite political oppression the number of refugees remained low due to relative stability.

The Derg Era (1974–1991): Political unrest and mass escape

The overthrow of Emperor Hale Serassier and the rise of the DERG junta in 1974 marked an important turning point in the history of Ethiopia's migration. Two months later, the government executed dozens of political enemies, sparking a new wave of immigration. The Qey Shibir campaign led to a civil war that continued until the collapse of Derg in 1991. This period overlapped with hunger in the mid-1980s, causing deaths of over a million people. The Ethiopian War with Somalia at Ogaden (1977-1978) further strengthened the massive displacement. By 1980, more than 2.5 million Ethiopians had been forced to evacuate, many of them sought evacuation in Sudan and Kenya, and had resettled in Western countries such as the United States, Europe and Australia.

Hunger in the mid-1980s made the crisis even worse. The international community's response, coupled with the oppressive political situation, has prompted many Ethiopians to migrate to Europe, North America, and the Middle East. In particular, the United States has become a major destination, and important Ethiopian communities have been formed in cities such as Washington, DC and Los Angeles.

Post-Derg period (Gifts from 1991): New challenges and shift patterns

Following the collapse of the DERG in 1991 and the establishment of the Revolutionary Democratic Front for the Ethiopian People (EPRDF), Ethiopia entered a period of political stability, allowing the rebound of more than 970,000 refugees from neighboring countries. However, economic challenges such as high unemployment and poverty have driven new migration trends.

In the early 2000s, many Ethiopians began to migrate to the Middle East, particularly to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, for domestic service, construction and hospitality jobs. Immigrants send remittances home, but often face exploitative working conditions and abuse.

Ethiopia as a host country

In contrast to its role as a source country, Ethiopia is becoming a destination for refugees fleeing conflict and instability in neighbouring states. Ethiopia currently hosts refugees from South Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia. With over 900,000 refugees, it is one of the largest refugee hosting countries in Africa. These populations often live in camps and urban areas where access to resources is limited.

According to a report from UNHCR 2025, Ethiopia hosts a total of 1,075,079 refugees and asylum seekers, including 1,011,585 refugees and 63,494 asylum seekers. Women account for 52% of this population, while men account for 48%. The majority come from South Sudan (40%), followed by Somalia (34%), Eritrea (17%) and Sudan (9%).

Recent trends: 2015–2025

It is estimated that from 2015 an estimated 839,000 Ethiopians have moved abroad between 2015 and 2020. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reports that most were between 15 and 29 years old. Approximately 31% have moved to Saudi Arabia.

These trends were driven not only by political instability and local conflict, including the 2018 Tigray War, but also by high unemployment and limited economic opportunities, leading to internal evacuation of over 1.8 million people by 2020.

According to the World Population Review 2025, Virginia's Ethiopian population is 38,394 (0.44%), followed by Maryland, with 34,566 (0.56%). California (36,527), Minnesota (26,926) and Washington (25,937) also have large Ethiopian communities. The District of Columbia has the highest concentration (0.99%), while Arkansas has the lowest concentration at just 49 (0.002%).

New migration trends: youth and irregular migration

Recent migration has been increasingly youth-driven, motivated by economic difficulties, educational aspirations, and to escape political or social instability.

One surprising trend is the rise in irregular travel routes through the Red Sea and the Sahara. Migrants seeking to reach the Gulf countries and Europe face serious risks, including human trafficking, abuse and death. Many Ethiopians travel to Libya in hoping to cross over to Europe via a dangerous boat route.

Dangerous Journey: East Corridor

The Eastern Moving Corridors – Corridors to Djibouti, Yemen and Saudi Arabia are one of the fastest growing and most dangerous in the world. Thousands of Ethiopians attempt this route every year, often facing temptation, abuse, or death.

The report highlights tragic conditions along this path. Immigrants risk drowning, exploitation and targeted killing by border forces. The Guardian investigation has reportedly killed hundreds of Ethiopian migrants trying to cross the border, raising serious human rights concerns.