Confusion between pilots of the ATR 72-500 via AROUND has led crews to fly low levels through Guernsey Airport in the fog after violating the ban on approach.

Following service from Southampton on August 12 last year, the Lithuanian registered Jump Air aircraft operated in Orliny, Guernsey.

The captain believed the weather would improve along the way, but the visual range of the runway rarely met the 550m threshold in the I-approach category.

If the visual range criteria for the runway were not met, the approach ban was enacted, with aircraft under 1,000 feet prohibiting descending order.

The ban on this approach was intended to reduce the number of missed approaches implemented with minimal and reduce the risk that aircraft would be piloted at low levels with poor visibility.

After being forced to enter some retention patterns, while waiting for better condition, the crew had the opportunity to begin the ILS approach when the visual range of the runway rose to 550m.

However, this lift was temporary and my vision was deteriorating once again. According to the UK's Aviation Accident Investigation Division, the visual range of the runway did not exceed 450m during the final approach.

When the aircraft got off 1,750 feet with its final approach, the visual range dropped to 325m, still 1,540 feet to this level.

“Both crew members were aware of the ban on approaches, but they did not mention a brief description of the approach or included it in Brief,” the captain added that it may have returned to the prior understanding that regulations allowed them to continue to do so.

The first mate stated that this understanding was “not challenged.”

Despite the visual range of the runway being inadequate for the cat's ils, the ATR crew continued to descend below 1,000 feet, violating the ban on approaches.

Upon reaching a determined altitude of 536 feet, approximately 0.5 nm from the runway, both pilots acquired a visual reference to the land.

“However, there was confusion between us and the crew in communicating this,” the investigation says, which led to the assistant officer asking for a go-around.

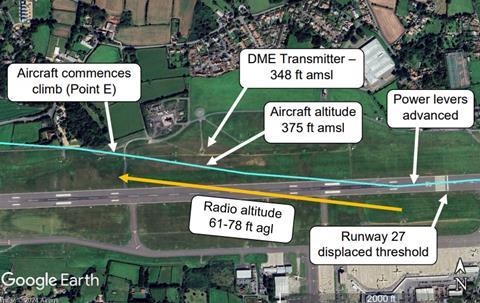

The captain began a go-around, asked for the flap to be withdrawn, and advanced the throttle lever to full power at 70 feet above ground, but the aircraft remained at level and did not climb.

In the next 15s, the aircraft flew through the 61-78-foot airport, deviated to the right side of the runway, coming within 40m sideways of the DME transmitter and within 27 feet vertically.

After travelling about 750m, the aircraft began climbing. The crew returned to Southampton and landed without further incident. None of the 57 residents were injured.

Cockpit-Voice Recorder information was overwritten and investigators had to rely partially on crew testimony to explain why the aircraft was delayed registration.

Research shows that “ineffective communication” meant that the pilot was also not convinced of the other's intentions just before the impasse.

When he began the go-around, the captain recalls demanding that the landing gear be withdrawn.

Research shows that the flight director would have shown a 7.1° nose-up pitch after the go-around button was pressed.

The assistant officer initially refused to take control, but said the captain urged him to climb without responding.

Eventually, the assistant officer pulled the control column himself to establish the climb, and the captain retracted the landing gear.

“The lack of a shared mental model among pilots has resulted in them not realising how close it is to the ground or how long the obstacles are,” the study adds.