Imagine living in a place where a single drought, hurricane, or landslide can wipe out food supplies. Many communities across Africa do just that. Navigates climate shocks such as floods, heat waves, and failure to harvest.

What is often overlooked in development policies to tackle these threats is Africa's own history, a powerful source of insight.

About 14, 700 to 5, 500 years ago, much of Africa experienced wet conditions. This is an era known as the moisture in Africa. The decline in wet conditions around 5,500 years ago led to major social, cultural and environmental changes occurring across the continent.

We are part of an interdisciplinary team of scientists who have recently published research into how they adapted to climate change over the past 10,000 years. This is the first study to investigate thousands of years of changes in people's livelihoods across the continent using isotopic data.

This continent-wide approach provides new insights into how livelihoods have formed and evolved across space and time.

Previous theories often assumed that society and its food systems evolved linearly. In other words, they have developed into a politically and socially complex society that hunts and brings together communities and practices agriculture.

Instead, what we see is a complex mosaic of adaptive strategies that help people survive. For 10,000 years, African communities have adapted by mixing pastoralism, agriculture, fishing and foraging. They blended a variety of practices based on what works in a particular environment at different times. Diversity in communities and throughout the region was key to human survival.

It has a real lesson in today's food system.

Our study suggests that strict top-down development plans, which include privileges to intensify agriculture than diverse economies, are unlikely to succeed. Many modern policies promote narrow approaches, such as focusing solely on cash crops. But history tells a different story. Resilience is not about choosing the “best” or most “intensive” method and sticking to it. Rather, they maintain flexibility and blend different strategies to suit local situations.

A clue has been left

We were able to develop insights by looking at the clues left behind by the food people ate and the environment they lived in. This was done and analyzed chemical traces (isotopes) of ancient human and livestock bones from 187 archaeological sites on the African continent.

Results were categorized into groups with similar functions or “isotope niches.” Archaeological and environmental information was then used to describe the ecological characteristics of these niches.

Read more: Tooth enamel provides clues regarding the spread of Tsetse flies and herding in ancient Africa

Our method illustrates a wide range of livelihood systems. For example, in today's Botswana and Zimbabwe, some groups combined small-scale agriculture and wild food gatherings with livestock herds after a humid period in Africa. In Egypt and Sudan, communities mixed crop agriculture focused on wheat, barley and legumes, with fishing, dairy and beer brewing.

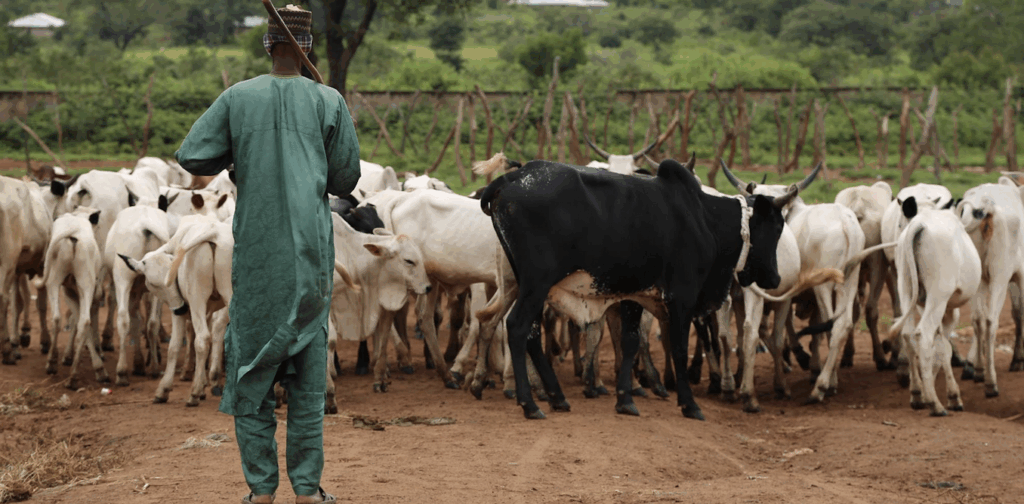

In particular, the Hermit developed a very flexible strategy. They adapted to hot plains, arid highlands, and everything in between. The idyllic system (farming with grazing animals) appears in more archaeological locations than any other food system. It also has the widest range of chemical signatures. It is evidence of adaptability to a shifting environment.

Our study also used isotopic data to construct photographs of how people use livestock. Most animal management systems relied on grasses (plants such as millet and tropical pastures) and were adapted to a wide variety of ecological conditions. Some systems were highly specialized in semi-arid and mountain environments. Others included mixed groups adapted to lower elevation regions. Otherwise, animals were kept as small inventory to supplement other livelihoods. We provided insurance against milk, feces and crop breakdowns.

Read more: Herding people are the world's asset – and we have a lot to learn from them

This adaptability helps to clarify why idyllic systems remain so important over the past millennia, especially in areas with increasing aridity.

Mixed Livelihood Strategy

This study also provides strong evidence of interactions between food production and foraging, whether at the community or local level.

Dynamic and mixed livelihood strategies were particularly evident during periods of climate stress, including interactions such as trade between close and distant communities. One of these periods was the end of a humid period in Africa (from about 5,500 years ago), when arid climates created new challenges.

In southeastern Africa, for 2,000 years, there has been a rise of diverse livelihood systems that fused herd, agriculture and foraging in complex ways. These systems may have emerged in response to complex environmental and social changes. It may have supported this development of resilience, with a focus on the complex changes in social networks, particularly land, resources and knowledge sharing.

Read more: Hunter-gatherer diets were not always heavy on meat: Moroccan research reveals a plant-based diet

How the past tells the future

Ancient Livelihood Strategy provides a playbook to survive today's climate change.

Our analysis suggests that over thousands of years, communities combining pastoralism, agriculture, fishing and assembly have made context-specific choices that help them navigate unpredictable circumstances. Rather than oppose them, they built food systems that work on land and sea. And they relied on strong social networks to share resources, knowledge and labor.

Past reactions to climate change can inform current and future strategies for building resilience in regions facing social and environmental pressures.

![]()

Leanne N. Phelps is a member of Columbia School of Climate at Columbia University. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, UK; Ngo Vaevae based in Andavadoke, Triara, Madagascar

Christina Guild Douglas receives funding from the National Science Foundation. She is affiliated with NGO vae vae.

This article was originally published in conversation. Please read the original article.