Time and again, commercial aviation has proven to be a very safe mode of transportation. As noted in the 2023 International Air Transport Association Annual Safety Report, 2023, the last year for which complete data is available, saw no fatal accidents or hull losses for jet aircraft worldwide. Despite several notable aircraft accidents in 2024 and early 2025, the number of airline fatal accidents worldwide in 2024 was just 16, according to FlightGlobal. The world’s airlines collectively carried 4.4 billion passengers in 2023.

In the United States alone, 2.9 million passengers flew out of US airports every day in 2024. There are 45,000 commercial and private flights per day.

When an aircraft goes down, a question can arise: Why does it take so long to remove an aircraft after a crash? Following a major multi-car accident on an American interstate, law enforcement and investigators can respond to, document and reopen the affected route in a matter of hours.

Commercial aviation disasters are different. The context of an aircraft incident or crash can be complex and diverse, from an inflight breakup to an aborted takeoff or a mid-air collision. Perhaps an incident involving equipment failure or human error, or both. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is the lead investigative agency for aircraft accidents. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Department of Transportation (DOT) Act that created the NTSB, an agency that would become independent of the DOT in 1974 to ensure “objectivity in its investigations and recommendations.”

The NTSB’s Office of Aviation Safety (OAS) investigates about 2,000 aviation accidents and incidents a year. The highly sequenced investigative process blends investigative diligence, scientific rigor, organizational management, public relations, and, importantly, compassion. Importantly, NTSB Regional Offices are responsible for implementing several notification procedures in their respective geographic areas of jurisdiction following an aircraft accident.

Several key factors are involved in the methodical process of responding to and investigating an airline accident or crash, or “hull loss” in aviation speak. These factors inform the often lengthy process of aircraft wreckage removal.

A disorienting and complex setting

The first priority is the rescue and recovery efforts for accident victims and the deceased at the crash site, the work of local first responders. Aircraft crashes are often spread over a sizable area, but not always. They present disorienting, complex and dangerous conditions during the initial hours.

The American Eagle CRJ700 collision with a Sikorsky UH-60 Army Black Hawk helicopter on January 29 near Washington Reagan Airport that resulted in the deaths of 67 people has been the lone fatal commercial aviation crash in the U.S. for the past 15 years. The collision left a relatively confined wreckage field in the runaway approach to Washington Reagan Airport. But that wreckage lay in the Potomac River, its dark waters, steady currents, and icy conditions making the investigation and rescue/recovery more difficult.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) accident investigation staff members, or Go Team, were able to arrive onsite that evening. Though the plane’s black boxes were recovered the following evening, it would take six days to recover all the bodies from the American Eagle CRJ700 wreckage.

Recovery efforts after a crash are often complex operations, more so when they are underwater. Several hundred responders from more than a dozen jurisdictions arrived on site in the initial days following the CRJ700-Black Hawk crash. Two Navy barges were brought to the site to lift heavy wreckage. The CRJ700 aircraft had a takeoff weight allowance of up to 75,000 pounds (34,000 kg).

The December 29 crash of a Jeju Air 737 800 at Muan International Airport (MWX) in South Korea also demonstrates the often lengthy and complex recovery and initial investigation process. The Boeing 737 skidded down the runway as it made an emergency belly landing, violently crashing into the airport’s localizer structure. The crash killed all but two of the 181 passengers and crew members onboard. The search for human remains took several days as responders combed the airport grounds and a nearby field filled with fragments of the aircraft.

A balance between reverence for human loss and the need for a thorough investigation requires crash scene fidelity before debris removal. This is not always an easy process for investigators or government authorities. Following the Jeju Air crash, several hundred grieving family members camped out at Muan International Airport for several days. Many were frustrated by the lengthy process to identify and return the remains of loved ones.

Related

Jeju Air Boeing 737 Struck Flock Of Birds Before Fatal Crash

South Korean investigators confirmed that both recorders stopped several minutes before the Jeju Air aircraft crashed at Muan International Airport.

Northwest Airlines Flight 255, a McDonnell Douglas MD-82, crashed shortly after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Airport DTW, in August 1987. The crash destroyed the aircraft and resulted in the deaths of all crew members and 148 of the 149 passengers. A sole survivor was eventually discovered in the wreckage hours later, a 4-year-old girl who was initially identified by authorities as a survivor from one of several vehicles that were destroyed when the doomed plane impacted two major access roads near the airport. The need for a thorough victim rescue effort is paramount.

Simultaneous to rescue efforts, NTSB Go Team staff and the team’s investigator-in-charge (IIC) are busy with their initial duties. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Major Investigations Manual Appendix further outlines two important steps for the investigator-in-charge:

Investigation and science

Maintaining the fidelity of the accident scene for the subsequent investigation is crucially important. As in a police homicide investigation, securing and documenting all critical physical evidence at a crash site is critical in establishing what precise events preceded the crash incident, in what sequence they occurred, and what can be learned from the event to prevent a repeat event.

Documenting the precise location and condition of a downed aircraft takes time at a wreckage site. Important on-site observations, documented in photos, written notes and videos, about the aircraft’s impact crater(s) and burn characteristics, for example, require that the wreckage remain as it was initially found for days or weeks.

An NTSB Go Team will be staffed with specialists in key areas like flight operations, engines, aircraft systems, air traffic control, metallurgy/materials, to name a few. Here, the organizational skills of the investigator-in-charge are critical. Beyond the technical analysis of aircraft equipment and debris, the NTSB investigative process must also include an examination of human performance issues, from operator incapacitation to hypoxia to substance impairment, to name just a few.

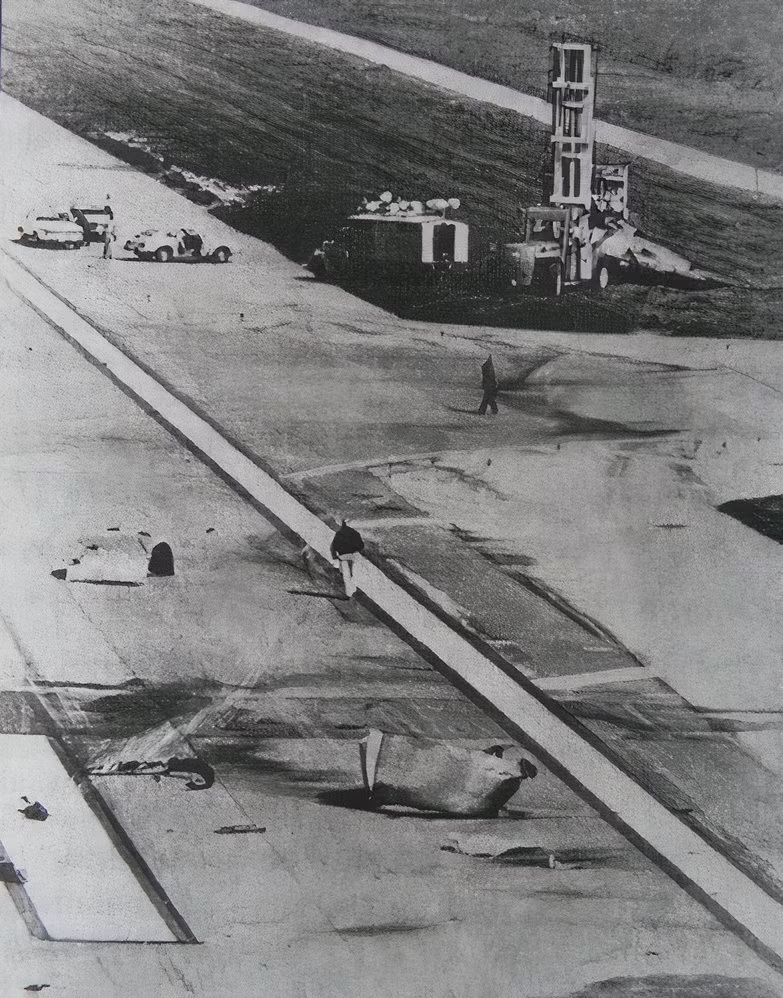

In May 1979, American Airlines Flight 191, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10, crashed on takeoff from O’Hare Airport in Chicago after its left engine had detached from the wing. The aircraft crashed about 4,600 feet (1400 meters) from the end of the runway, resulting in the deaths of 273 passengers and crew. After complex and lengthy metallurgy and metal fatigue analysis, the detached left engine and pylon provided key physical evidence about the sequence of events that led to the disaster. The burned and destroyed wreckage of the DC-10 represented just one element of the investigative narrative.

Photo: NTSB

In the U.S. and abroad, DC-10s were grounded for several weeks after the crash until it was established that the aircraft did not have a fundamental design flaw.

The seven-month NTSB crash investigation later determined that the sequence of events began with an engine change for the aircraft at the American Airlines maintenance facility in Tulsa, Oklahoma two months before the crash. Investigators determined that maintenance procedures led to fatigue cracking and bending damage to pylon mounts.

The clock is ticking

There are two competing needs—diligence in establishing the facts concerning the cause(s) of the crash while providing the public and key stakeholders with timely answers. NTSB staff must also work to secure hotel space that will serve as a command post, and public/press briefing space. It is worth noting that the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the UN agency tasked with establishing aviation safety and certification standards, requires accident investigators to produce a preliminary report within 30 days of the accident and encourages a final report to be made public within 12 months. The clock is thus ticking to produce a report and provide answers to the public while maintaining fidelity to the investigative process, no matter how long it takes.

Related

Black Boxes: Exploring The History Of Flight Recorders

Black boxes record data and audio for flights to help determine and reconstruct the events in cases of aircraft accidents.

Retrieving the flight data recorder (FDR) and the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) is a priority. NTSB staff know where to locate the bright orange devices on crash sites. New versions use solid-state memory chips and boards that can yield crucial flight characteristics data even when damaged by fire or impact. But again, it can take days or perhaps weeks to extract and interpret complete flight data, which, when combined with well-documented on-scene physical evidence, can answer crucial questions about the precise sequence of events that led to the crash.

Following the December 29 Jeju Air 737 crash, Korean aviation investigators with the country’s Aviation and Railway Accident Investigation Board (RAIB) were joined by NTSB investigators and staff from Boeing. After the plane’s black boxes were recovered, South Korean aviation investigators deemed the data irretrievable with local technical resources. The flight data recorder would be sent to the United States for analysis by the NTSB lab.

A complex multi-party event

The NTSB, just like aviation investigative agencies in other nations, has the discretion to designate other organizations and entities (contractors, aircraft manufacturers, airport authority representatives, for example) as parties to the investigation. These designated party members can often provide expertise to the investigation and, like the aforementioned American Air 191 accident, add crucial context to the investigation. It can also extend the length of an investigation.

Related

When Does The NTSB Participate In International Airline Crash Investigations?

When accidents abroad involve US-made or registered planes and operators, the NTSB will get involved.

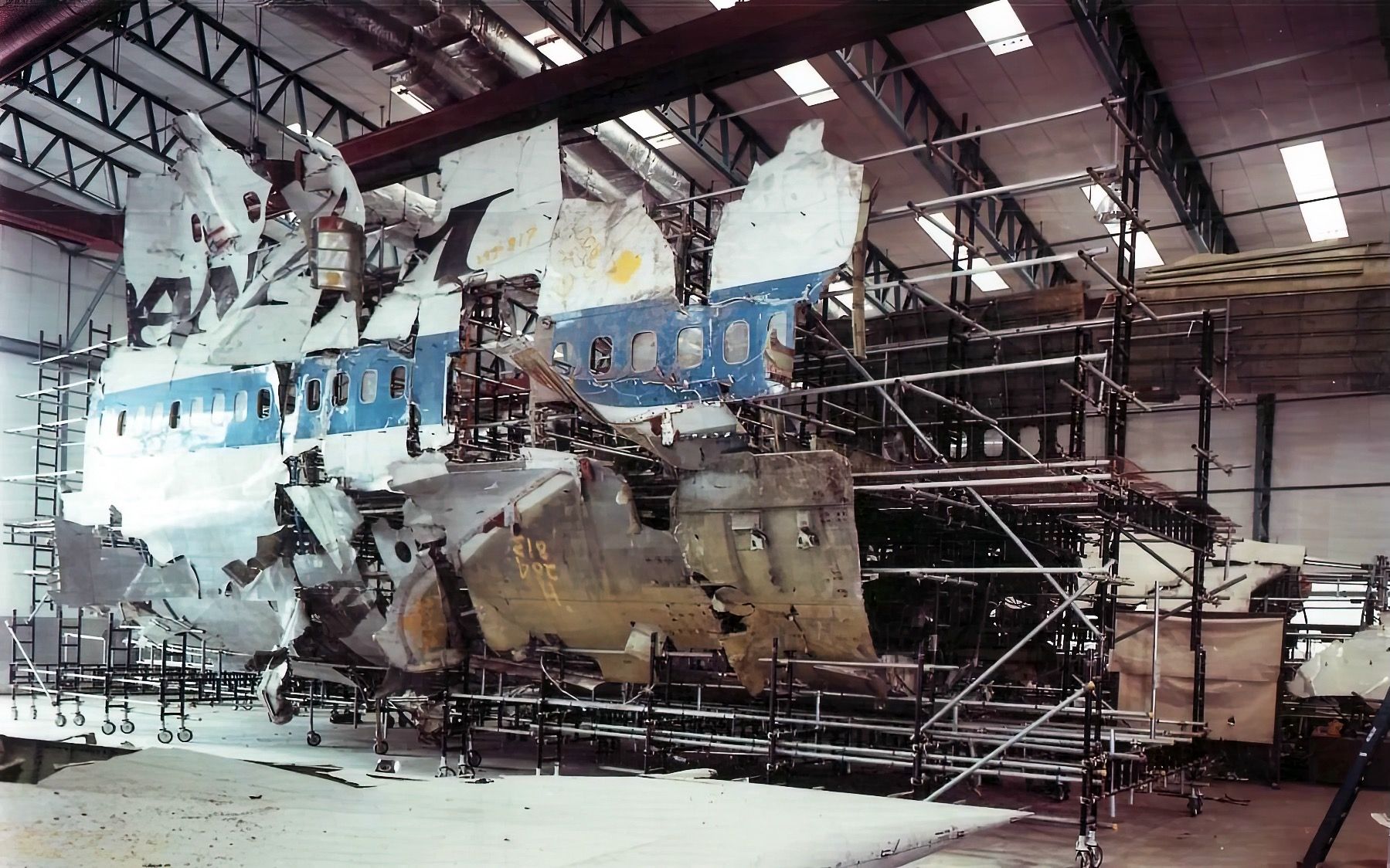

Additionally, the collection and investigation of aircraft crash debris can become a particularly lengthy process when international flights are involved or when criminal activity is involved. Pan Am Flight 103, a 747-121 en route to JFK Airport, exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland in December 1988. All 259 people onboard the aircraft were killed as well as 11 Scottish citizens on the ground.

So began one of the largest and most lengthy criminal investigations as flight recorder data and examination of the wreckage revealed that the aircraft suffered sudden decompression and broke apart as it fell to the ground.

Solving the bombing required international cooperation between several government entities, most notably the UK Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB), Scottish police and prosecutors, and the FBI. The explosion occurred at 30,000 feet and rained debris over 845 square miles, creating perhaps the largest-ever crime scene. Investigators recovered 319 tons of wreckage, and much of it remained in place in Lockerbie and the surrounding area for weeks to establish a sequence of events for the aircraft’s demise.

Investigators eventually discovered charred scraps of cloth, including one with a fragment of a bomb circuit board. Based on flight recorder data and physical evidence, British investigators reassembled a specific portion of the fuselage at an AAIB facility at Farnborough Airfield in Hampshire, England. The investigation led to the indictment and trial in 2000 of two Libyan men for their role in the bombing.

“And every time you try to decide from the looks of the thing (an aircraft crash) what happened, you find out in the conclusion of the investigation you were wrong.”

— ABC-TV reporter Jim Slade on the Pan Am 103 disaster, December 1988

The saga of Pan Am 103 wreckage reinforces the importance of crash site fidelity and patience during the investigative process. Though the criminal investigation involving the bombing would continue for decades, the AAIB Pan Am 103 crash report came nearly eight months after the tragedy. Does the wreckage matter after the initial investigation? Yes. Just last December, a key section of the aircraft wreckage was brought to the US for the upcoming trial of the Libyan man accused of making the bomb—thirty-seven years after the incident.

Debris removal and recommendations

The investigative process continues for several months, including public hearings. An NTSB accident report can include agency oversight, airline operations, and general safety recommendations. Beyond the NTSB hearings, which often occur six months after a major crash event, hull loss insurance coverage and passenger litigation issues will also arise.

The NTSB investigator-in-charge must decide what to do next with all or parts of the wreckage. Influencing that decision is the role that wreckage may play in any future government, aviation, civil or criminal proceedings. As highlighted by the Pan Am 103 investigation, this point is not academic.

Additional considerations related to aircraft removal and recovery are the unique salvage equipment often required to remove a downed aircraft. Fuselage lifting systems or a wing-tethered lift system may be required. It’s a methodical process: The maximum takeoff weight for a Boeing 737-7, for example, is 177,000 pounds (80,000 kg).

Photo: NTSB

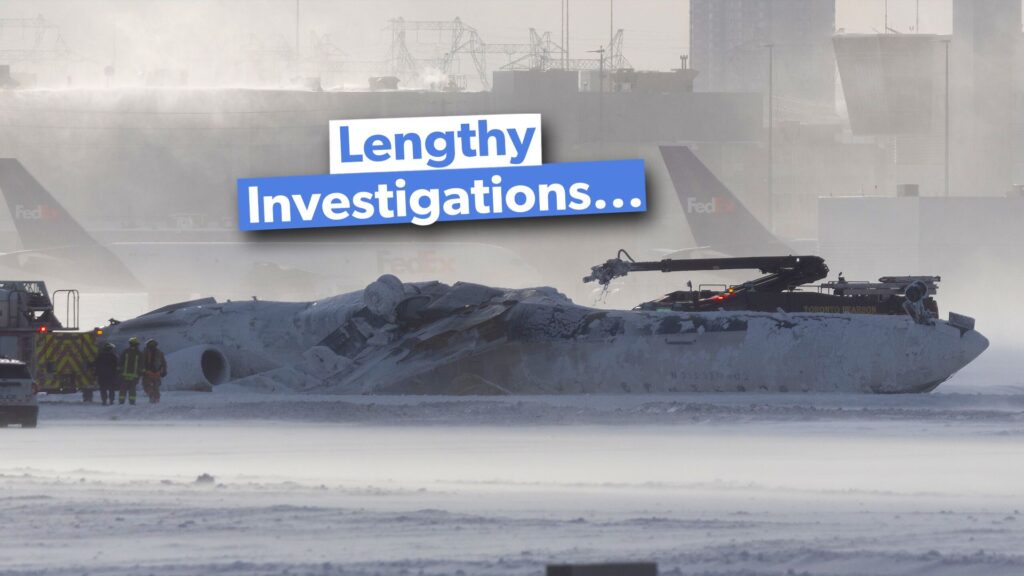

The wreckage of Endeavor Air 4819 was removed from runway 23 at Toronto Pearson Airport about 55 hours after the February 17th crash. The removal process was aided by a crash site that was located on airport property and the rapid retrieval of the flight data recorders from a fuselage that was mostly intact, and no fatalities.

Related

Delta Crash In Toronto: Canadian Transportation Safety Board Updates On Investigation

The TSB said that it already has sent the two recorders, known as the black box, for analysis.

An important observation about crash wreckage and the need for ongoing investigative diligence can be found in the NTSB Major Team Investigations Manual:

“There should be no pressure to release all of the on-scene wreckage. Often it is better to arrange for wreckage removal and storage and to retain control of the wreckage in case there is a need to examine it later.”