African hypothesis. Human dispersal to East Eurasia: A need for research into ancient genomic insights and physiological adaptation. Credit: Journal of Physiological Anthropology (2025). doi:10.1186/s40101-024-00382-3

Researchers at the University of Tokyo investigated the origins and dispersal scenarios of Homo sapiens to East Eurasia. The team looked at how transition routes, genetic contributions from archaic humans, and environmental adaptation helped form modern populations, and found unlikely flaws in one idea of origin.

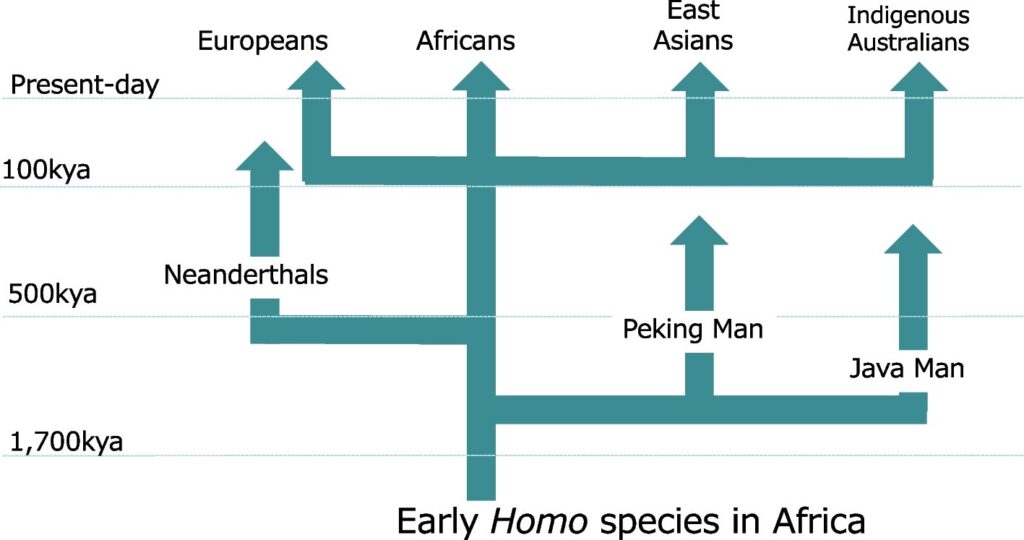

The origin and dispersion of Homo Sapiens has been debated, even narrower, between two major competitive models: the multi-physical evolution model and the Out of Africa model.

The model from Africa suggests that homo sapiens are born in Africa, distributed globally, and remained the dominant scientific consensus in the last 30 years, primarily due to advances in genomic research.

The multifaceted evolutionary model proposes that modern humans evolved simultaneously from archaic groups in multiple regions. A major flaw in the multifaceted evolutionary model is the possibility that there are no identical mutations that lead to brain expansion independently in multiple populations around the world.

Although multifaceted evolution was previously considered in western academia, it is now most associated with Chinese anthropologists and archaeologists, supporting the idea that modern East Asians evolved directly from local archaeological humans, such as the Beijing (Homo erectus pekinensis), rather than from the African Homo sapiens. This view is partly influenced by early fossil discoveries in China and a more nationalist interpretation of human origin.

In this study, researchers published in “Human Dispersion to East Eurasia: The Need for Research on Ancient Genome Insights and Physiological Adaptations,” Journal of Physiological Anthropology applied genomic analysis and archaeological assessment to assess migration patterns and physiological adaptations.

Whole genome sequences for both modern and ancient populations were used to determine the dispersion pathway to East Eurasia. We analyzed mitochondrial DNA, nuclear DNA from autosomal and sex chromosomes, and paleoenomic data from Neanderthals and Denisovan.

The researchers also examined physiological adaptations such as cold resistance, metabolic shifts and photosensitivity through genomic variants.

Genomic evidence from large projects, including the HAPMAP project and the 1000 Genomes Project, confirmed that a common ancestor who left Africa about 60,000 years ago shares a modern non-African population.

This study also confirms that the African population has the highest genetic variation and supports the African origins of all modern people.

This study investigated two possible pathways of travel into East Eurasia. The north route passing north of the Himalayas and the south route passing through the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia before arriving in East Asia.

Genetic studies, particularly from the Pan-Asian SNP consortium, strongly support the southern route as the main migration route for modern East Asian ancestry, including Han Chinese, Japanese (except Yomon's ancestors), and many Southeast Asian populations.

Genomic analysis of the people of Jomon, an ancient Japanese population, shows that modern East Asians lacks a significant Northern route genetic contribution, whereas Native Americans and Northeast Asians do. The Northeastern groups include the Siberian, the Mongolian population, and several indigenous groups from China, South Korea and Japan.

Heritability from Denisovan and Neanderthals played an important role in physiological adaptation, including cold resistance, metabolism and immune function. TBX15/WARS2 and UCP1 affected thermogenesis, while Neanderthal DNA contributed to immune defense, pigmentation, and circadian rhythm regulation.

The cold adaptation of the TBX15/WARS2 gene from Denisovan is associated with thermogenesis and body fat distribution and can be found at high frequencies between East Asians and Inuit. East Asians whose ancestors endure Siberian winters have higher basal metabolic rates and may reduce their risk of obesity compared to other populations.

Denisovan also contributed to the EPAS1 gene, which promotes high altitude adaptation in Tibetan people.

The neanderthal insertion genes in the OAS gene cluster enhanced the antiviral immune response. Pigmentation genes inherited from Neanderthals helped to regulate to reduce ultraviolet exposure in the north latitude.

Ancient genetic adaptations that once gave the benefits of survival can contribute to modern health issues such as obesity and risk of type 2 diabetes. The th-about gene hypothesis suggests that cold adaptive genes that promote fat storage are at a disadvantage in modern environments with abundant food availability. Genes inherited from the Neanderthal SLC16A11 are associated with a higher risk of diabetes, particularly in the Mexican and Latin American populations.

While modern East Asians prove that they have come down mainly from southern route immigrants, Native Americans and Northeast Asians show a mix of north and south ancestry, all with arrows pointing to Africa's starting point.

More information: Steven Abood et al, Human Dispersion to East Eurasia: The Need for Research on Ancient Genomic Insights and Physiological Adaptations, Journal of Physiological Anthropology (2025). doi:10.1186/s40101-024-00382-3

©2025 Science X Network

Quote: Testing of the Outside Africa Model of Genome Origins in East Eurasia (March 4, 2025) Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2025-03-africa-east-eurasian-genomic.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair transactions for private research or research purposes, there is no part that is reproduced without written permission. Content is provided with information only.