It's hard to believe that 1,300 people were working almost alone, where I stand now, on the frozen hillsides at the edge of the mountain range. It is the almost precise point where the densely populated valleys and cities at the edge of southeastern Wales begin with the mountains and wide open countryside in one of the most populous parts of the UK.

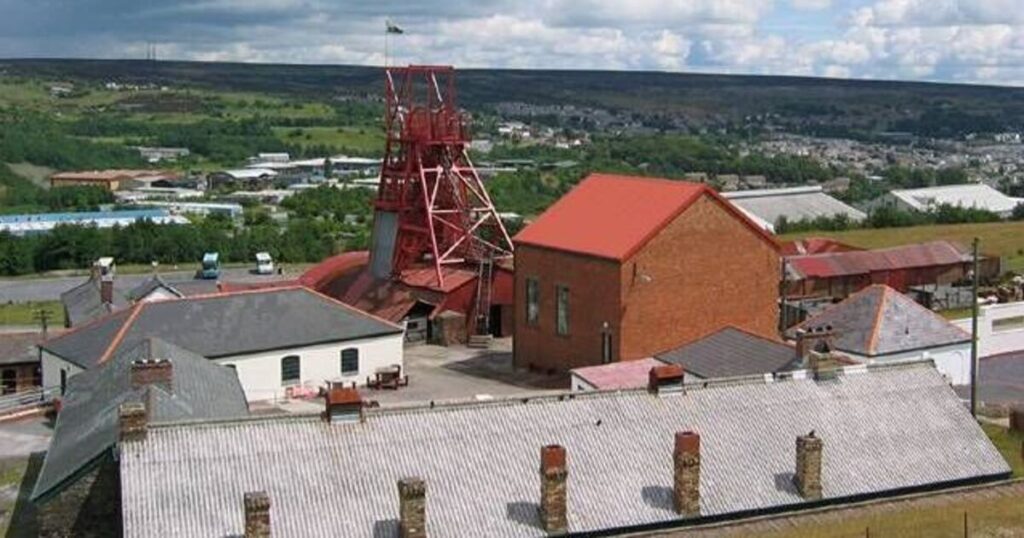

The view from here is usually beautiful. The Brecon Beacon is only just north, with the valley of Wales in the south, but even the Red Mining Winch Tower, a symbol of the history of this part of England today, becomes completely invisible despite the fact that I stand only a few meters away from it.

This is Big Pit, the National Coal Museum in Brenavon, which brings the history of the industrial history that has been built in most of modern Wales and the UK: Coal. And it does a very good job, so it is named the best free charm to visit in Wales and is one of the best in the UK.

And what a history that is. Without a place like the Big Pit, there are not many parts of the UK as we know them today. Cardiff would not have grown even if places like Brenavon, Melsir and Ronda Valley had sent millions of tons of coal to cities that had been one of the world's largest coal exporters for some time.

Mining began in the Big Pit in the 19th century, and it has been 45 years since coal was pulled out of the ground. Today, some of today's sites look like things fell when they finally stopped production in 1980. It's tough but beautiful. In 2000, it was chosen as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the wider Brenabon Industrial Area, in recognition of its role as one of the world's leading iron and coal producers.

Today's big hole tells the story of the coal mine and how it took shape in modern Wales. The original coal mine buildings include a winding engine house, a blacksmith shop and a pithead bus installed in 1939.

Hundreds of lockers are stacked in line, with many telling stories of individual miners and officials, not only working here, but also family stories. I was walking around with my 4-year-old son and 9-year-old daughter, and it's a phenomenal and calming fact that children of my age worked in this mine and others.

It also shows that the health and safety of miners was once merely a cloth hat and a “scarf above the mouth.” And this despite the fact that the mine was a fatal place where hundreds of men and boys could die (in 1913, 439 people died in the Sengenid Coal Mine Disaster, a few miles south of here).

Records show that the medical assistants, cited in the 1842 mining report, stated that “children are employed as horse drivers, age 5, 14, and horse drivers, age 12, as horse drivers.” “It's rarely seen as a rare occurrence for a child to work at a young age of five and a half,” said a mineral agent at a nearby Mercer mine.

It is almost impossible to imagine a 5-year-old sitting in the darkness of the pitch for up to 12 hours on one job (or faint flickering from an oil lamp). Doors can be opened and closed for airflow, moving around the mine, allowing miners and coal mines to pass away.

Standing in the mine itself makes it even more difficult to imagine. This was a suspected highlight of a visit, a 90-meter descent of the metal cage that once was the heartbeat center of this place, with a vast network of tunnels in the mines, underground (but not as deep as deep mines). The walking tour is full of information and views, despite touching on only a few of what actually exists here. I wear a helmet with headlamps, but it's hard to imagine a dark place anywhere, when I turn everything off at some point with the guide's instructions. My thoughts go back to those kids.

Also, there is a whole stable complex here for the pit pony. This has roughly the same individual stalls as you can find on the farm, except that it is 90 meters underground. Each food stall will continue to carry the names of the ponys who worked here for 50 weeks a year.

The tour was led by a former miner and this was what made my day. He was an outstanding guide and was fascinating, interesting and proud of the parts that both he and this place perform in our history. He remembered my child's name roundly, talked to Polish tourists in their language, and didn't even get frustrated when my 4-year-old decided to take a headlamp from his helmet and drag it along the mine floor instead. He visited. I can't recommend the big pit enough. It feels like everyone who cares about the UK today needs to see it.

(Blaenavon is also home to Blaenavon Heritage Railway, which operates beautiful steam and heritage diesel services over the weekend between April and September. We didn't visit this time, but it's worth taking into account the visit).