Aramie

AramieThe simple drink has become the country's go-to appetif ever since absinthe was banned as rumors led to insanity.

It's difficult to imagine France without Apello (Apelichif time). At a magical moment when time stops, then suddenly, everyone is holding a drink in their hands.

In countries that are extremely proud of their local products, it's no surprise that the contents of the aperitif vary from Burgundy blackcurrant KIR to Belgian border beer to pastis with cloudy anise from Marseille. But despite its strong relationship with the southern part of France, one apello spirit is ubiquitous in France, despite reminiscent of the image of a lazy summer afternoon playing Petanque at sea: pastis. Pastis sales represent a fifth of all spirits sold nationwide, as well as the default Aparichiff drink north to Picardy.

“It's not like some of the predator plants in other regions,” said Forest Collins, author of the book Drink Like a Local: Paris. “Pineau des Challenz, you are primarily going to find around the cognac. Pomôme, you are primarily going to find in Normandy. But anywhere in France you may find a bottle of pastis.”

Aramie

AramieHowever, Pastis did not become the French go-to Abelichiev by design. Without the ban on absinthe in 1915, due to its detrimental effects and the marketing chops of Paul Ricardo in Marseilai, herbliqueur may not have become the most famous in France.

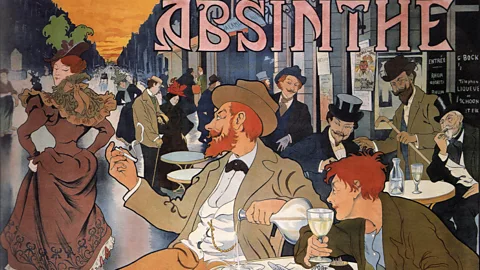

The quiet conquest of France in Absinthe was triggered by the 19th century plant leaf epidemic, wiping out almost half of the country's vineyards. Soon it replaced northern wines as well as beer, Normandy cider, and wines with flavours like Quinquina, and Marie-Claude Delahay, founder of the book L'Absinthe: Histoire de lafé everet and Muséedel'Absinthe e explained. auvers-sur-oise. According to Delahier, the absinthe was introduced along with a “playful and cheerful ritual” in which anise was introduced into anising, diluting 75% ABV liquid with sugar and water.

“It was a bud of something that could be extraordinary success,” Delahie said. However, the rise in absinthe fame was hampered in 1915, when it was banned nationwide following rumors that it led to insanity in 1915. The enthusiasts soon began screaming for something to fill the gap in the scent of the anise. “If absinthe had continued to be commercialized, Pastis would never have appeared,” Delahai explained.

While Pastis and Absinthe share Anise's flavour profile, the similarities halt there. Distilled absinthe is more complicated than sweetened soaked pastis, and at 40-45% ABV, the alcohol power of pastis pales in comparison. According to Collins, this gave Pastis the advantage. Absinthe was considered “drinks of degenerated artists” (including Eduardo Manet, Edgar Dega, Henri des Toulouse Latrec and Vincent van Gogh,” she said. of painting). Meanwhile, in Pastis, drinkers still have “that nice little topic and its lovely anise flavour” without any negative connotations.

Aramie

Aramie“I think that's the effect Pastis has had on the aperitis culture,” Collins said. “Anis' drinking culture has been able to continue.”

When you order pastis at most cafes, it is poured from a bottle decorated with a bright yellow sun and one name, Ricardo. But before Ricardo was there, there were two Pernods to be exact. Both Henri Lewis Pernodo and Jules Felix Pernodo released Aniset in 1918 and merged the company in 1928. Meanwhile, Ricardo began selling versions in 1932. chop. He immediately appealed to the French love of the Terroir, and derived his Anizet name from Provenzal Pastison (mixed), and made his recipe “a poacher who knew all the herbs of the mountains and all the herbs of the galligurug…” I returned to it. He soon set out to spread the story through door-to-door visits to bistros and cafes throughout France.

Apelo's method

Apelo times are usually between 18:00 and 19:30. French squares and terraces are filled with groups sipping on beer, pink kills and pastis golden demis. Cafes usually offer free bowls of potato chips, pretzels or olives along with a complimentary apello, but food is second only to drinks and conversation. Apello is not drunk, and it is not uncommon for a friend to nurse drinks for an hour before letting go of the way to have dinner at home.

“He used to say, 'Make friends in a day,'” said Gabriel Alevikian Zerri, brand director at Pernod Ricardo.

Perhaps Ricardo's most successful initiative was the merchandise. Amateur artist Ricardo has created posters for the brand that evokes Sunny Marseille, not to mention glasses, ashtrays and bucket hats and hats. He released thousands of such objects on the 1948 Tour de France. Today they are ubiquitous in French flea markets, where avid collectors track them down.

Aramie

AramieJacky Roussial is one such collector. For more than 39 years, Roussial has accumulated over 3,500 Ricardo brand objects, including 180 different goblets, playing cards and umbrellas. His most precious pastis possessions are Pitchett Tambourine, a “Collector's Holy Grail,” depicting the 1950s pitcher Tambourine player. It costs about 4,000 euros.

These pitchers are more than just trinkets. They are an important part of serving pastis and are drinks that can be customized with design. Each 2cl pour is intended to be diluted with water for taste. Many people sweeten pastis with syrup. A bright green mint and pastis blend is called peroke (parrot), and the addition of grenadine makes tomatoes (tomatoes). Of these, according to Alevikian Xerri, Mauresque (a blend of Pastis and Local Southern Orgeat) is the most popular.

In recent years, modern mixologists have bullied them by creating more complex pastast cocktails. Margot LeCarpentier, a cocktail bar combat in Paris, blends with Cachasa to highlight the floral notes, while Aurely Panhelks, co-founder of both Marseille and Paris Copperbay Cocktail Bars, has also been known for his work, and has been working on the gin, lemon. Created juice, permeated augerts and CITRON, House Moleco. However, according to Collins, these works remain anecdotes at best, and he attempted to create a pastis-scented play in the popular Aperol Spritz about a decade ago, but “it actually happened.” Not there.”

“I think the traditional method is how most people drink pastis,” she said.

Even Lecarpentier agrees. “Ninety-five percent of French people would say Pastis is drunk with a glass of water and an ice cubes,” she said. “It's strange not to serve that way.”

Aramie

AramiePastis is ritualized until the drinker lightens the spirit with water from the brand's pitcher, takes on the cloudy yellow tint, and adds syrup and ice to the flavor. According to Collins, the relatively simplicity of how Pastis is served – especially compared to absinthesinthe, dripping into the glass via sugar cubes set in a special perforated spoon, the drink's permanent It's some of the popularity. “Everyone in their home can have a small pitcher, but not everyone goes outside and gets an absinthe fountain and an absinthe spoon,” she said.

Pastis' accessibility solidified its place as an aperitif to dominate all aperitif. Whether men and women, old or young, Pastis is more than anything else: “To unite people.

“Pastis is a matter of preference, often a matter of tradition,” Panheryu said. “In France, that is the only spirit that was ordered by brand.”

Aramie

Aramie“I don't drink pastis,” Lucial echoed. “I'm going to drink Ricard.”

Part of the drink's popularity comes from the fantasy Ricardo, which was still made. “This is a typical symbol of the sun, the holidays, the Mediterranean, the far Niente (art of doing nothing),” Lucia said. But meaning aside, for Collins, its appeal comes from its ubiquitous presence more than anything.

“For most people, it's just a way of life. It's almost like (table wine),” she said.