Empowering individuals and communities to have control over their health and wellbeing is increasingly becoming one of the fundamental principles of public health policy, practice, and research (1). Consequently, health literacy promotion across vulnerable population groups, including refugees has aimed to enable sovereign decision-making and self-determination (2). Health literacy is linked to health care access and care-seeking behaviour (3,4,5), chronic disease management (6, 7), health outcomes and mortality (8), and medical and health system costs (9, 10).

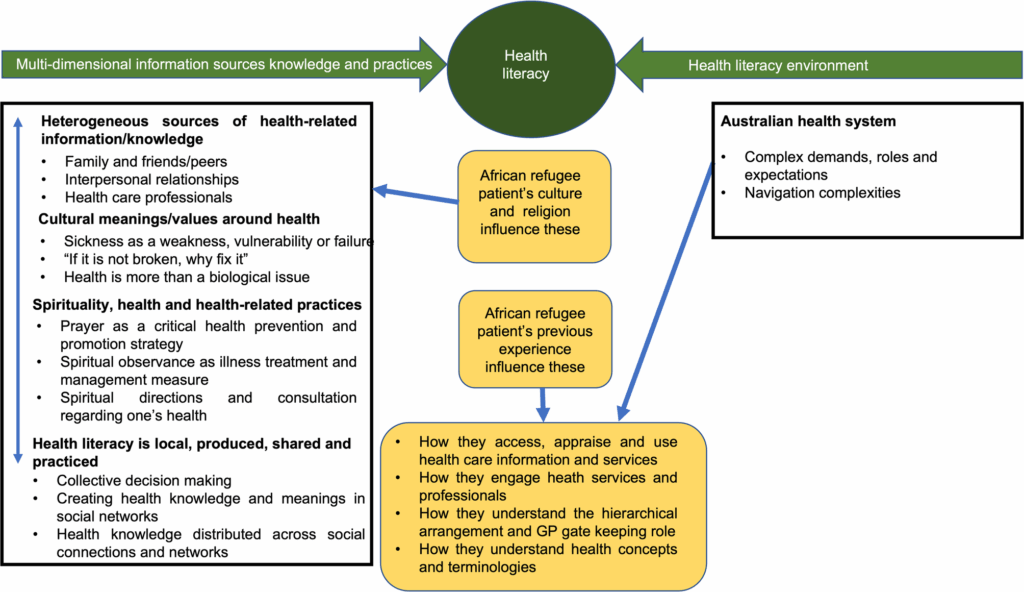

Conceptually, health literacy as complex concept has been variously defined, measured, and applied (11,12,13). Initially, the concept was commonly conceptualised as an individual ability to find, comprehend, and use health information (13, 14). This definition has been considered as a traditional and deficit model of health literacy (15, 16). This is because it considers health care users as literate when they are able to read, write and understand and act on health-related information (16). As the concept continues to evolve, different components, definitions and models of health literacy have been developed (13, 17). This study draws on the accounts of Nutbeam’s (14) critical/analytical health literacy and health literacy as a social practice (18,19,20). Thus, this study defines health literacy as a dynamic, context-specific concept that includes multidimensional skills and abilities, knowledge practices, and information sources that enable people to care for themselves and others (14, 19, 20).

Recently, the environmental dimensions of health literacy, including the infrastructure, policies, people as well as relationships of the health care system that influence how people and communities navigate their own and others’ health, have received policy and scholarly attention (21, 22). This dimension of health literacy encompasses social skills, relationships and health service environments that support health and care-seeking behaviours and decisions (1). Thus, the development of health literacy can be reframed as a dynamic and interactive process between individuals, communities, and the health care system (23,24,25).

Similarly, others have argued that health literacy is usually distributed across social connections and relationships (20, 26). These conceptualisations indicate that health literacy constitutes health knowledge applicable to everyday life— not only patient-oriented knowledge in health care environments (27). These new conceptualisations also reveal that health literacy is entwined with broader sociocultural determinants of health and is shaped by complex array of factors, such as culture and language (24, 28).

Indeed, Sørensen et al. (13) in their comprehensive model of health literacy based on a review of definitions and models of health literacy, reported that a network of intersecting factors, including cultural beliefs and language, collectively shape health literacy abilities. In support, various scholars have argued that health literacy as a dynamic and multidimensional concept is influenced by several factors, including language, norms, belief systems, practices, and values (27, 29, 30). According to the American Institute of Medicine (31), health literacy must be conceptualised in the context of language and culture. Vass et al. (32) further supported this assertion by arguing that worldview and language are the “linchpins that determine advancing health literacy” in contexts such as refugee communities where English is a second language. This conceptualisation suggests that culture, language and health literacy are closely connected concepts (27).

Individuals’ cultural belief systems, norms, values, and practices influence their health knowledge source and application (20). Other researchers have argued that cultural literacy is a critical domain of health literacy, suggesting that individuals, including patients and health professionals, knowledge, practices, and understanding of health are connected to their cultural beliefs, customs, norms, and identities (33,34,35,36). Thus, in the context of culturally diverse groups such as African refugees, the elements of culture (defined as a pattern of learned beliefs, values, and behaviours shared within a group), including language, communication styles, practices, customs, and views on roles and relationships (37), could be potentially critical mediating factors in the acquisition and application of health literacy skills and abilities more than factors such as gender and age (1, 38,39,40,41).

People define health and illness and respond to health information, messages, and treatments through a cultural lens (40, 42). Cultural norms, belief systems, and practices influence health care seeking behaviour, how symptoms are described, which treatment options are considered and from whom, and whether treatment is chosen and adhered to (33). Similarly, within health professional groups and organisations, social and cultural practices influence how they engage with and respond to the health knowledge and practices of people from culturally and linguistically diverse groups, such as refugees (34).

Although health literacy studies are increasing in Australia (43), previous research has tended to focus on assessing individuals’ health literacy skills, developing models, validating measures, and evaluating the readability of patient health information and materials based on Western constructs and concepts. There is only minimal research currently exploring intersections between health literacy, culture, language, and experiences, particularly among cultural groups such as refugees. Others have indicated that this is one of the areas where further research is required because health literacy resides in individuals, communities and health services/systems (20, 27, 44). In two studies in the United States of America (USA) and Canada (27, 41), language, cultural beliefs and practices influence the health literacy and health practices of refugees.

These studies show that cultural norms and language shaped understanding, navigation and experiences of the US and Canadian health systems and services. Also, among Indigenous populations in Australia, some studies have demonstrated the effect of sociocultural differences on health literacy (1, 40, 45, 46). Unfortunately, such evidence is limited in Australia among refugees, particularly those from African countries who are culturally and linguistically diverse. Refugees’ construction of health literacy, which explicitly incorporates cultural lenses (27) and their experiences with the health care system, are mainly undocumented in Australia. A deep scholarly understanding of the influences on health literacy is essential to reducing health inequities in refugee health.

This paper explores how African refugees in Australia 1) understand and navigate the Australian health care system; 2) may have specific cultural norms, beliefs and language that influence their health literacy practices (including everyday strategies, activities and actions to promote/maintain health and well-being based on their health knowledge and understanding) in Australia; and 3) take concrete actions and decisions to enhance their health literacy and health in response to the norms, roles, and expectations of the Australian health system. Study findings have implications for how systems and organisations can respond to the health literacy and cultural needs of refugees.

Overview of African refugees

African refugees comprise 30% of all humanitarian entrants in Australia (47) and this population is heterogeneous (48, 49). They are culturally, ethnically, and linguistically diverse (49,50,51). Within one African cultural group, several norms, practices, values, and dialects can be found (52). Apart from cultural diversity, many African refugees have interrupted and fragmented educational histories due to extended camps. Most of this population is from non-English-speaking countries, including Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia and Sudan. Upon arriving in their new countries, including Australia, they are mostly illiterate in their first language and English. Although language support services exist, such as interpreting services, the ability of this population to be aware of and navigate Australian medical systems, communicate effectively with service providers, and access services, especially in the initial stages of resettlement, can be limited (52).

Irrespective of African refugee groups’ cultural and linguistic diversity, common experiences exist among them regarding the role of culture, community, religion and spirituality in their health and health care (53, 54). African refugees share information within groups and family and connectedness to each other are sources of identity and support among African refugee communities (55). Family, peers, and community support remain critical to successful resettlement and access to services, including health among African refugee groups and communities (54). African refugee groups network with and rely on one another for health and health-related knowledge and information. For instance, family and peers remain the first port of call for support, including health, among many African refugees (55). Studies have also shown that within African refugee communities, the need to maintain, adhere to and preserve cultural belief systems, norms, expectations, and practices is critical (51, 56). These cultural beliefs and practices may define where, when and from whom to seek health care and support as African refugees seek to retain their cultural knowledge and practices (55).

Many African refugees’ notions of health and well-being are largely dependent upon two factors: religion and spirituality (38, 39, 57) and these factors guide and influence all aspects of their lives. As a heterogenous group, African refugees adhere to diverse religious faiths and practices, particularly Islamic and Christian beliefs, and practices (38, 51). Religious practices promote community and well-being (54). Many African refugees, through their religious and spiritual inclinations, believe that ill health is caused by external forces that can be controlled or prevented through activities such as demonstration of one’s faith via prayer, reciting the Bible and Quran, application of ingredients such as herbs as advised by Prophets and traditional healers and observance of cultural customs and norms (57,58,59). As a result, religious leaders such as Pastors, Imams, traditional spiritual healers/herbalists, and community leaders/elders are seen as influential individuals with traditional and spiritual knowledge, information, and responses to health challenges (60). Thus, religious beliefs and practices may influence health literacy and health practices because faith-based activities are mechanisms this population use to maintain health and well-being.

African health systems and the Australian health systems

Equally important, many African refugees in Australia come from an entirely different health system that has different navigation and access complexities. Although African countries are diverse regarding cultural beliefs, ethnicity and language, there are several commonalities among health systems in many African countries (61, 62). For instance, many health systems in Africa have no hierarchical arrangements, such as the gatekeeping role of General Practitioners (GPs). In many African health systems, patients have direct access to specialised services and do not need an appointment before seeing a provider. In addition, health systems do not require patients to have digital knowledge to book online appointments or find and access online health information. Thus, many African countries’ health systems and services regard patients as dependent or passive care recipients (58).

These characteristics contrast with Australia’s health systems, which are highly complex, layered, and hierarchical and ultimately consider individuality, independence, and agency in health-seeking (63). Therefore, these characteristics of Australian health care systems assume that patients must have adequate knowledge and understanding of the systems and services to be active partners in seeking and providing care. This may lead to a mismatch between the health system and service literacy skills and abilities of African refugees and the requirements of the Australian health care system and services.

The profile of African refugees and the differences in African and Australian health systems provide space to explore: how does health literacy influence African refugees’ experiences and practices in Australia; how does health literacy change? how do they use their health literacy to work around services?